|

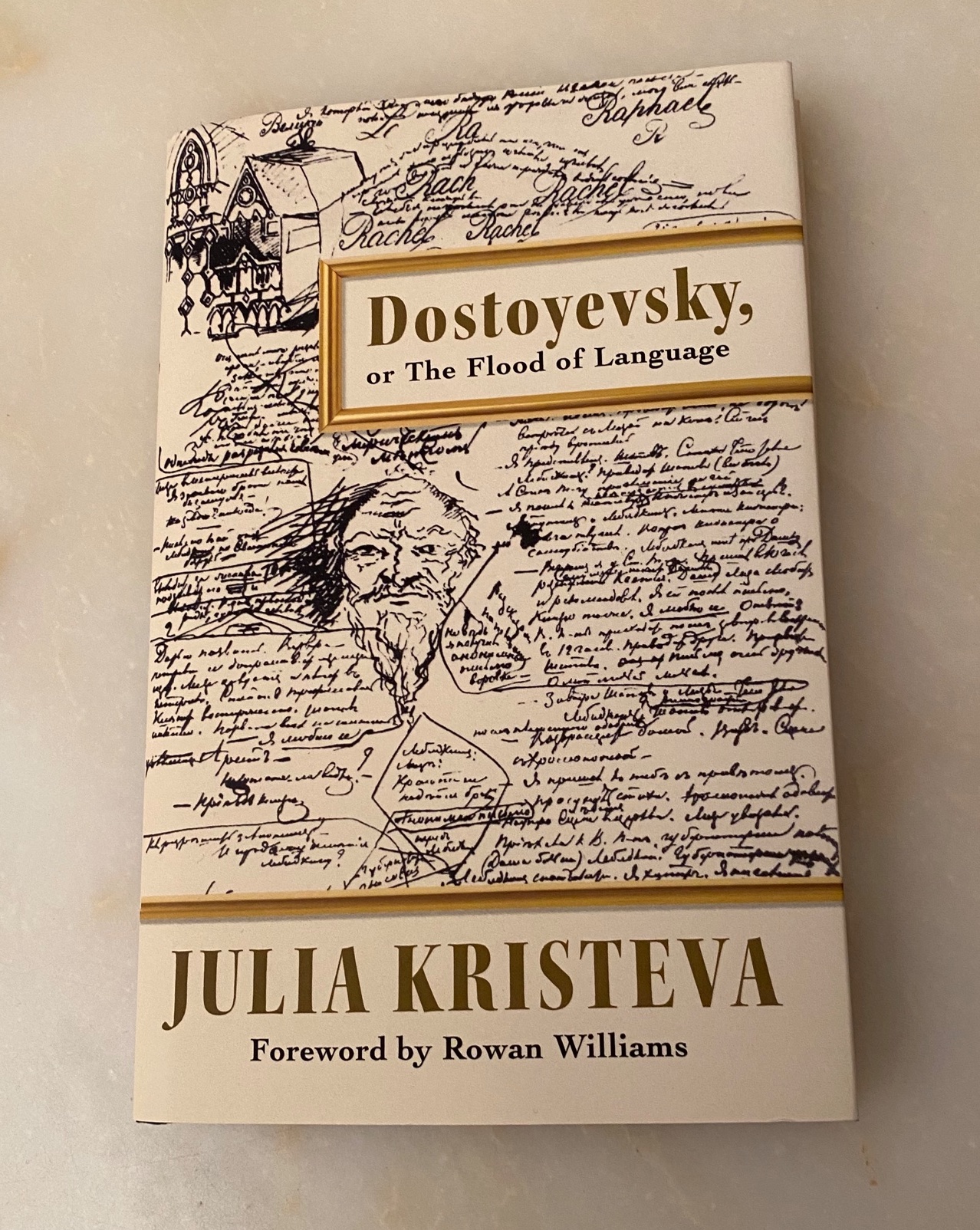

Dostoyevsky, or The Flood of Language

Julia Kristeva. Translated by Jody Gladding. Foreword by Rowan Williams.

Columbia University Press

Growing up in Bulgaria, Julia Kristeva was warned by her father not to read Dostoyevsky. “Of course, and as usual,” she recalls, “I disobeyed paternal orders and plunged into Dosto. Dazzled, overwhelmed, engulfed.” Kristeva would go on to become one of the most important figures in European intellectual life—and she would return over and over again to Dostoyevsky, still haunted and enraptured by the force of his writing.

In this book, Kristeva embarks on a wide-ranging and stimulating inquiry into Dostoyevsky’s work and the profound ways it has influenced her own thinking. Reading across his major novels and shorter works, Kristeva offers incandescent insights into the potent themes that draw her back to the Russian master: God, otherness, violence, eroticism, the mother, the father, language itself. Both personal and erudite, the book intermingles Kristeva’s analysis with her recollections of Dostoyevsky’s significance in different intellectual moments—the rediscovery of Bakhtin in the Thaw-era Eastern Bloc, the debates over poststructuralism in 1960s France, and today’s arguments about whether it can be said that “everything is permitted.” Brilliant and vivid, this is an essential book for admirers of both Kristeva and Dostoyevsky. It also features an illuminating foreword by Rowan Williams that reflects on the significance of Kristeva’s reading of Dostoyevsky for his own understanding of religious writing.

Part spiritual autobiography, part free association, Kristeva’s study of Dostoyevsky becomes the occasion for a journey through the life of the mind. In searing harmony with her subject, she once again demonstrates how it is only out of the depths of abjection that human creativity is born. One of her most exuberant and challenging works, Dostoyevsky, or The Flood of Language offers us Dostoyevsky as lascivious, blasphemous, and saint, taking us into the core of Kristeva’s unique vision. Jacqueline Rose, author of On Violence and On Violence Against Women

Dostoevsky, as Kristeva’s reminder about language and the sacred helps us guess, loves religious mischief precisely because he cares so much about religious faith. Michael Wood, London Review of Books

Dostoyevsky scholars will find this worth a look. Publishers Weekly

CONTENTS

Kristeva’s Dostoyevsky: The Arrival of the Human, by Rowan Williams

Preface

Can You Like Dostoyevsky?

Crimes and Pardons

The God-Man, the Man-God

The Second Sex Outside of Sex

Children, Rapes, and Sensual Pleasures

Everything Is Permitted

Notes

Index

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Kristeva is professor emerita of linguistics at the Université de Paris VII and author of many acclaimed works. Her most recent Columbia University Press book is Passions of Our Time (2019).

Rowan Williams, the former archbishop of Canterbury, is the author of many books, including Dostoevsky: Language, Faith, and Fiction (2008).

Jody Gladding is a poet who has translated dozens of works from French, including Kristeva’s The Severed Head: Capital Visions (Columbia, 2014).

https://cup.columbia.edu/book/dostoyevsky-or-the-flood-of-language/9780231203326

Kristeva's

Dostoyevsky: The Arrival of the Human

by

Rowan Williams

…

Julia Kristeva's reading of Dostoyevsky is, in effect,

a tour de force of linking this particular novelist's practice with the

fundamentals of the psyche as a linguistic reality. It is a reading that pulls

together the impact of the familiar Bakhtinian theme of Dostoyevsky's

"polyphonic" method, the centrality of dialogical exchange, and the

less fully explored idea of the narrative writer as consciously holding

themselves and the reader on the verge of the "empty center" of

speech. They are in fact perspectives that belong together: if the essence of

Bakhtinian dialogue is that everything and everyone is "at the

frontier" of its opposite, this means that any determinate identity in the

speech- world will be shaped by its refusal of what it is not; it is

haunted by the unrealized potential of what has not been chosen and spoken. A

dialogical and polyphonic form of "telling" allows a to- and- fro between what is said and not- said, what is chosen and

what is denied, by voicing different speakers. And Dostoyevsky is famously in

love with creating pairings, twinnings between

characters— most dramatically perhaps with Myshkin/ Rogozhin and Nastasya/Aglaya in The Idiot and with the images of abusive

and nurturing fatherhood in Fyodor and Zosima in Karamazov.

...

One of Kristeva's basic insights is thus to do with

what Dostoyevsky's fiction tells us about writing itself, and narrative writing

in particular: the significant and durable fiction is one in which we are aware

of the central void at the origins of speech and the touch that crosses it— not

a touch uniting two isolated substances but one that constitutes substance and

subject precisely in that moment. As the subject develops from this

point, it can remain "in touch" with the originating touch only by

the deferral and mediation of desire, which steers away from any collapse into

a "fruition" that is simply the absorption of otherness into

sameness. And our relations with other desiring subjects, both taught by

them and contesting them, are all in one way or another involved with

negotiating these deferrals and mediations so that they sustain life.

…

ROWAN WILLIAMS, Excerpted from the Foreword : Kristeva’s Dostoyevsky: The Arrival of the Human.

Can You Like Dostoyevsky?

Julia Kristeva

Eyes fixed

on the Bulgarian editions of The Idiot(1869), Demons (1872),

and The BrothersKaramazov (1880), my father

advised me strongly against reading them: “Destructive, demonic, clinging, too

much is too much, you won’t like him at all, let it go!” He dreamed of seeing

me escape “the bowels of hell,” as he called our native Bulgaria, quoting some

obscure verse in the Holy Scriptures. To fulfill this desperate plan, I only

had to develop my “innate taste” for clarity and freedom, according to him, in

French, of course, since he had introduced me to the language of La Fontaine

and Voltaire. In addition to the language of our “great Russian brother,” which

was imposed upon us “naturally.” At that time, the ruling ideology taunted the

“religious obscurantism” of the writer, “an enemy of the people,” even though,

behind the Stalinist scenes, devoted specialists continued to extol his

mysteries with a passion: his “immersion” (proniknovenie) in self and

other (Vyacheslav Ivanov), the “plurality of his worlds” in the manner of

Einstein (Leonid Grossman), his “Shakespearean polyphony” (A. V. Lunacharsky),

and so on. Of course, and as usual, I disobeyed paternal orders and plunged

into Dosto. Dazzled, overwhelmed, engulfed.

I will never

forget the staggering effect of reading the two conversations between

Raskolnikov and Sonya and their exchange of the cross in Crime and Punishment (1866).

Did she guess that he himself did not really know what he had done? Crime or

delirium, the murder of Alyona Ivanovna, lowly pawnbroker and “rich as a Yid,”

had wrested the “detective novel” from popular literature and revealed the

wretchedness and abjection of our century. And the cross that the nervous

student rejected and then finally accepted: Was it Sonya’s cross or in fact the

one she had received from Liza, the second victim?

This gift of

a gift, this pardon, did he link it—both fascinated and disgusted—with his own

feminine tendencies? To succeed with the revival of his hero’s destiny, with

“Napoleon in view,” Rodion hallucinated the ultimate freedom of a “louse”

becoming “superman” by murdering a superfluous human being.

“Everywhere

and in all things I lived at the ultimate limit, and I spent my life surpassing

it,” Dostoyevsky wrote to his friend A. N. Maykov in that same period (1867). I

could understand, envy, question. But living in the

text, this jostling of norms and laws to the point of obliterating the

“ultimate limit”? I was in over my head.

Later,

rediscovering Dostoyevsky in French, I stumbled onto a passage in A Writer’s Diary(1877)

mentioning the fate of a neologism of his own invention, which he had

introduced in The Double (1846) and which

Turgenev, his unbearable and admired rival, had used abundantly since: stushevatsya (“to

disappear,” “to annihilate,” from the Russian tush, in German Tusch,

referring to India ink). The engineering student who applied himself to

sketching various drafts, plans, and military constructions, drawn and washed

with India ink, excelled in the art of “reducing a dark drawing to white and to

nothingness.” “Imperceptible erasure into nonbeing,” like the evasive,

vanishing subject that was the young Dostoyevsky himself. To one who wished to

hear it, his neologism revealed the exquisite excitement retained in the

written gesture, the extenuated sound of his voice engraved in the map of the

mother tongue, the sensual pleasure of being “the wound and the knife,” the

sharp stylet that scarifies, control and collapse conjoined. Or how to

“annihilate oneself with fluidity.”

But it is

neither an “elegant ink wash” nor a painting on Chinese silk that stushevatsya produces

as penned by Dostoyevsky. That word permeates the pitiful embraces of the elder

Golyadkin and his double, the younger Golyadkin (The Double,

1846). It oozes into the “sin” that pierces

them, tickles the fleeting “glance,” brushes against the

crowd that “surrounds” them, then “gives way”

delightfully, like “pâté in the mouth”

of its shadow, substitute filth. . . . In the discreet polyphony of this

neologism, I thus perceived what A Writer’s Diary (1877)

did not say but what the novelistic swell of the entire opus insidiously sweeps

along with it: the triumphant expansion of sentences released with the last breath

(tush in Russian also means “fanfare”); the convulsive saraband of

consumed bodies (“tusha” refers to “flesh” and “meat”; “tushit’”

means “extinguish” or “smother”); seductions, lures, and the sensual pleasure

of the catch; or the caressing pictorial technique. In French, toucher (“to

touch”) is charming when we find something “touching” or are “touched” by it

but becomes questionable in faire unetouche (to

hit on someone). Irrefutable pleasures of writing.

The young student of French philology and comparative

literature did not know that she was captive to this tushenie / stushevatsya. I

was knocked flat. And I ran to find again my La Fontaine, Voltaire, and Hugo,

which would lead me to Sartre, Beauvoir, Camus, Blanchot, the nouveau roman,

Sollers. An exile as exhausting as hard labor underground in Dosto’s white

nights, but different. Sharp-edged intoxication of pleasure, lucid sublimation

of French, in French, and risky freedom as singular transcendence.

Then the second edition of the book by Mikhail Bakhtin, Problems of Dostoyevsky’s Poetics(1929–1963),

appeared in Russian, a major event for specialists, amateurs, and many others.

This was the thaw. The promised freedom of thought was slow to

arrive, but it crept into literary theory and criticism, secret lung of a

suffocated philosophy.

The initiated had been familiar with the first edition for a

long time, but with this new one, Bakhtin’s Dostoyevsky became a social

phenomenon, a political symptom. At the center of this new furor was my friend

and mentor, Tzvetan Stoyanov, well-known literary critic, anglophone,

francophone, and obviously russophone. He had already introduced me to

Shakespeare and Joyce, Cervantes and Kafka, the Russian formalists and the

breakthrough postformalism of a certain Bakhtin. Now we could reimmerse

ourselves, day and night, out loud and in Russian, Bakhtin’s book in hand, in

the novels of Dostoyevsky. I heard the vocal power of tragic laughter, the

farce within the force of evil, and that contagious, drunken flow of dialogues

composed as story that Bakhtin calls slovo, translated as mot (word)

in French. Through the vocabulary and syntax, I heard, as Logos incarnate, the

Word stirring biblical deliverance into a new multivocal, multiversal

narration:

“I am full of words, the spirit within me constrains me;

inside I am like wine that has no vent, like wine that bursts from new

wineskins! I will speak, that I may find relief, I will open my lips and reply!

I will show no partiality nor flatter anyone, for I do not know how to flatter,

else my maker would soon take me away” (Job 33: 18–22).

Job’s cry, recounts the writer, must have already pierced

the eardrums of the baby Fyodor, nestled in his mother’s arms.

The Russian formalists knew how to examine carefully the

labyrinths of story, and they would inspire French structuralism.

Illuminating analyses, against which the Bakhtinian approach rebelled;

attentive as it was to Hegel even while rejecting Freud, tuned into “popular

comedy” and “Rabelaisian laughter,” it attempted to elucidate the sorcery and

toxicity of narrative poetics according to Dostoyevsky.

In the novelistic slovo (“word”), in the

Bakhtinian sense, this theorist’s interpretations locate a profound logic: that

of the dialogue. The human voice arises from dialogue:

initial, inexhaustible, unresolvable conversation. I only ever

speak in twos, a fundamental alterity-proximity. We converse with

one another. A stabilizing-destabilizing structure because “dialogue allows the

substitution of one’s own voice for that of another.” From which

identification and confusion follow. But also projection, introjection, and

sometimes reciprocities: invasive or fruitful, closed or open, murders or

ecstasies. The narrator finds himself alone there, but only just, because he is

not really the author but another kind of dialogist, a sort of third party who

risks getting mixed up in the story, which proceeds from the dialogue and is

composed of thresholds, impasses, and dramatic twists, repeatedly, ad

infinitum.

The dialogue becomes, with Dostoyevsky, the deep structure

of the way of being in the world,

“everything is at the border of its opposite”: meaning crumbles but is

restored, masked-unmasked, carnivalesque misalliances, and dark, pensive

laughter. Necessarily, inevitably, “love lives on the very border of hate,

knows and understands it, and hate lives on the border of love and also

understands it” (as with Alyosha Karamazov).

In renewing a current that runs through European literature,

Dostoyevsky invents an “original and inimitable form, totally new, the polyphonic novel.”

On the one hand, he manages to “carnivalize” ethical solipsism; since humanity

cannot do without the awareness of others, the opposites that divide

(life-death, love-hate, birth-death, affirmation-negation) also tend to

contract and converse in the “the upper pole of a two-in-one image.” Example:

Prince Myshkin, a brilliant carnival figure, saint and idiot. His mad love for

his rival Rogozhin, who has tried to assassinate him, reaches its height after

the assassination of Nastasya Filippovna by that same Rogozhin, when the final

moments of princely consciousness give way to insanity.

But, on the other hand, the polyphonic novel also opens the

private scene and its defined era to the space of a universal infinity,

the aim of the mysteries as early as the Middle Ages, and

evoked by the important explanation of Shatov and Stavrogin in Demons (1872):

“We are two beings, and we have come together in infinity . . . the last time

in the world. Drop your tone, and speak like a human being! Speak, if only for

once in your life, with the voice of a human.”

...

JULIA KRISTEVA

Excerpted from Dostoyevsky,

or The Flood of Language by Julia

Kristeva. Translated by Jody Gladding. Copyright © 2022

Columbia University Press. Used by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights

reserved

https://www.bookforum.com/culture/the-grand-inquisitor-24770

|