November 29, 2008

100th-Birthday Tributes Pour in for Lévi-Strauss

By STEVEN ERLANGER

PARIS — Claude Lévi-Strauss, who altered the way Westerners look at other civilizations, turned 100 on Friday, and France celebrated with films, lectures and free admission to the museum he inspired, the Musée du Quai Branly.

Mr. Lévi-Strauss is cherished in France, and is an additional reminder of the nation’s cultural significance in the year when another Frenchman, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Mr. Lévi-Strauss shot to prominence early, but with his 1955 book, “Tristes Tropiques,” a sort of anthropological meditation based on his travels in Brazil and elsewhere in the 1930s, he became a national treasure of a specially French kind. The jury of the Prix Goncourt, France’s most famous literary award, said that it would have given the prize to “Tristes Tropiques” had it been fiction.

Mr. Lévi-Strauss, a Brussels-born and Paris-bred Jew, fled France after its capitulation to the Nazis in 1940. He spent the next eight years based in the United States, where he taught at the New School for Social Research in New York and was influenced by noted anthropologists like Franz Boas, who taught at Columbia.

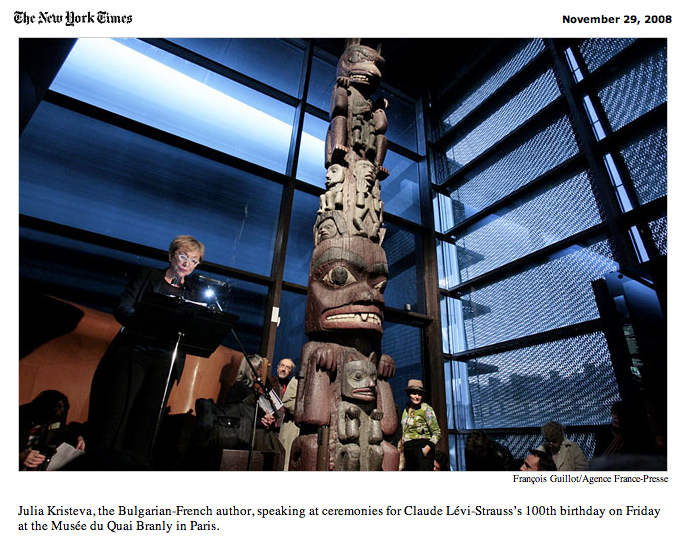

On Friday, the culmination of several days of celebration, there were no false notes. At the Quai Branly, 100 scholars and writers read from or lectured on the work of Mr. Lévi-Strauss, while documentaries about him were screened, and guided visits were provided to the collections, which include some of his own favorite artifacts.

Stéphane Martin, the president of the museum, said in an interview that Mr. Lévi-Strauss was himself a major collector, and as he first toured the new museum, in 2006, “he remembered various pieces and complained that he had to sell them to pay for a divorce.”

Mr. Martin, along with the French culture minister, Christine Albanel, and the minister of higher education and research, Valérie Pécresse, presided over the unveiling of a plaque outside the museum’s theater, which is already named for Mr. Lévi-Strauss, who did not attend the festivities. Ms. Pécresse announced a new annual 100,000 euro prize (about $127,000) in his name for a researcher in “human sciences” working in France. President Nicolas Sarkozy visited Mr. Lévi-Strauss on Friday evening at his home.

Roger-Pol Droit, a philosopher who read from “Tristes Tropiques,” said that he “would have loved a text from Lévi-Strauss today saying, ‘I hate birthdays and commemorations,’ just as he began ‘Tristes Tropiques’ saying, ‘I hate traveling and explorers.’ “

“This is all about the effort of making him into a myth,” Mr. Droit continued, “because that is what we do in our time.”

The museum was the grand project of former president Jacques Chirac, who loved anthropology and embraced the idea of a colloquy of civilizations, as opposed to the academic quality of the old Musée de l’Homme, which Philippe Descola, the chairman of the anthropology department at the Collège de France, described as “an empty shell — full of artifacts but dead to themselves.”

The new museum, which has 1.3 million visitors a year, was a sort of homage to Mr. Lévi-Strauss, who “blessed it from the beginning,” Mr. Descola said, and was an important voice of support for a much criticized and politicized idea.

In 1996, when asked his opinion of the project, Mr. Lévi-Strauss said in a handwritten letter to Mr. Chirac: “It takes into account the evolution of the world since the Musée de l’Homme was created. An ethnographic museum can no longer, as at that time, offer an authentic vision of life in these societies so different from ours. With perhaps a few exceptions that will not last, these societies are progressively integrated into world politics and economy. When I see the objects that I collected in the field between 1935 and 1938 again — and it’s also true of others — I know that their relevance has become either documentary or, mostly, aesthetic.”

The building is striking and controversial, imposing the ideas of the star architect Jean Nouvel on the organization of the spaces. But Mr. Martin says it is working well for the museum, whose marvelous objects — “fragile flowers of difference,” as Mr. Lévi-Strauss once called them — can be seen on varying levels of aesthetics and serious study. They are presented as artifacts of great beauty but also with defining context, telling visitors not only what they are, but also what they were meant to be when they were created.

On Thursday, from noon to midnight, ARTE, a French-German cultural television channel, showed nothing but Lévi-Strauss, with documentaries, films and interviews with him and with those inspired or influenced by his work, including the novelist Michel Tournier.

The French Academy, which governs the French language and elected Mr. Lévi-Strauss in 1973, honored him in what its permanent secretary, Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, called “a huge event and perhaps above all ‘a family celebration.’ “

On Tuesday there was a day-long colloquium at the Collège de France, where Mr. Lévi-Strauss once taught. Mr. Descola said that centenary celebrations were being held in at least 25 countries.

“People realize he is one of the great intellectual heroes of the 20th century,” he said in an interview. “His thought is among the most complex of the 20th century, and it’s hard to convey his prose and his thinking in English. But he gave a proper object to anthropology: not simply as a study of human nature, but a systematic study of how cultural practices vary, how cultural differences are systematically organized.”

Mr. Levi-Strauss took difference as the basis for his study, not the search for commonality, which defined 19th-century anthropology, Mr. Descola said. In other words, he took cultures on their own terms rather than try to relate everything to the West.

Mr. Descola, 59, said he was 17 when he read “Tristes Tropiques,” and “it left a lasting mark.”

“I can’t say I decided on the spot to become an anthropologist,” he said, “but rather to become a man like that.”

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Quai Branly is its landscaping, designed by Gilles Clément to reflect the questing spirit of Mr. Lévi-Strauss. Mr. Clément tried to create a “non-Western garden,” he said in an interview, “with more the spirit of the savannah,” where most of the animist civilizations live whose artifacts fill the museum itself.

He tried to think through the symbols of the cosmology of these civilizations, their systems of gods and beliefs, which also animate their agriculture and their gardens. The garden here uses the symbol of the tortoise, not reflected literally, “but in an oval form that recurs,” Mr. Clément said.

“We find the tortoise everywhere,” he continued. “It’s an animal that lives a long time, so it represents a sort of reassurance, or the eternal, perhaps.”

Mr. Lévi-Strauss “is very important to me,” Mr. Clément said, adding: “He represents an extremely subversive vision with his interest in populations that were disdained. He paid careful attention, not touristically but profoundly, to the human beings on the earth who think differently from us. It’s a respect for others, which is very strong and very moving. He knew that cultural diversity is necessary for cultural creativity, for the future.”

Basil Katz contributed reporting.

Copyright 2008 The New York Times Company