|

||

|

|

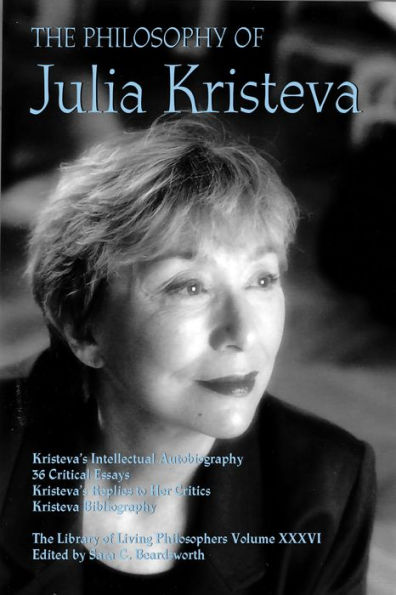

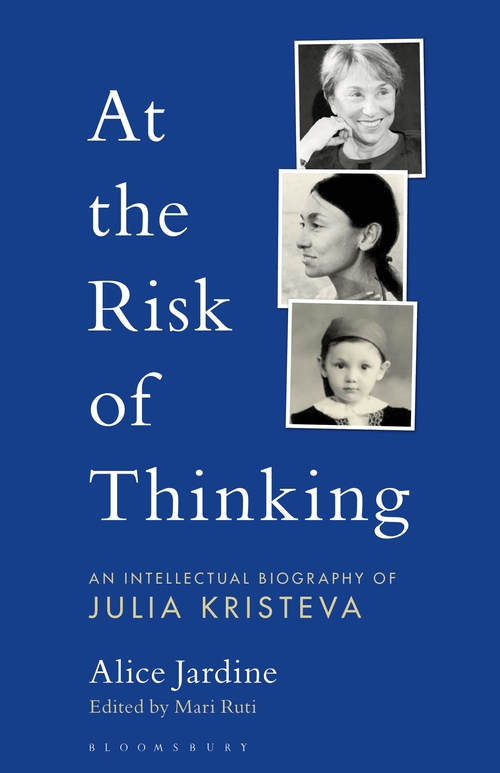

Thinking with Julia Kristeva On the occasion of the publication of The Philosophy of Julia Kristeva, ed. Sara G. Beardsworth, in The Library of Living Philosophers, Open Court Publishing Company, 2020 and of At the Risk of Thinking: An Intellectual Biography of Julia Kristeva, by Alice Jardine, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020. Participants: François Noudelmann, Kelly Oliver, Alice Jardine, Noelle McAfee, Maria Margaroni, John Lechte, Lauren Guilmette, Karen Mock, Miglena Nikolchina, Emilia Angelova, David Uhrig, Samuel Dock, Ewa Ziarek, Fanny Söderbäck, Cecilia Sjöholm, Elaine Miller, Robert Harvey, Marian Hobson, Sarah Hansen, Rachel Boue, Julia Kristeva in conversation with François Noudelmann.

Vidéo: 0:00:00:00 Welcome and

Introduction, François Noudelmann

00:02:06 Dear Julia

Kristeva

00:08:43 Panelists

for initial discussion, Julia Kristeva: The Life – Biography/Autobiography

/Fiction Roundtable

00:08:57 Moderator

Kelly Oliver’s opening remarks

00:10:23 Alice

Jardine, author of the biography “At the Risk of Thinking”

00:16:46 Questions

to Panelists

00:17:38 Noelle

McAfee

00:21:28 Maria Margaroni

00:26:25 John Lechte

00:33:05 Lauren Guilmette

00:37:03 Karen Mock

00:40:49 Miglena Nikolchina

00:50:02 Emilia Angelova

00:59:22 Noelle

McAfee’s questions to Alice Jardine

01:13:10 François Noudelmann & Alice Jardine

01:14:00

Introduction to conversation with Samuel Dock and David Uhrig

01:14:17 David Uhrig

01:15:05 Reading

text – Powerpoint presentation – David Uhrig

01:25:37

Conversation in French between David Uhrig and Samuel

Dock, on the autobiographical interview with Julia Kristeva, “Je me voyage “

01:54:36 Part 2

01:57:54 Ewa Ziarek

02:06:03 Fanny Söderbäck

02:11:24 Cecilia Sjöholm

02:16:54 Elaine

Miller

02:25:12 Robert

Harvey

02:34:16 Marian

Hobson

02:41:06 Sarah

Hansen

02:47:03 Rachel Boue

02:59:49 Questions

(François Noudelmann) to Julia Kristeva

03:01:01 Julia

Kristeva on her work in conversation with François Noudelmann

03:56:00 Questions

from audience

04:09:09 Closing

remarks

|

Thinking with Julia Kristeva

Conversation entre Julia Kristeva et François Noudelmann

François Noudelmann: The fabulous book dedicated to your work has been published in the series The Library of Living Philosophers. When critics try to define you, they hesitate between psychoanalyst, semiotician, writer, and philosopher. Of course, you are all of these definitions and more, but could you say something about your identification with, or relationship to, philosophy? Even if there is not a single definition of philosophy, could you say what role it has played, through major or minor philosophical references, in your thinking?

Secondary question: There are not many women in philosophy. Does being a woman philosopher imply adopting a phallic writing?

Julia Kristeva: Dear François Noudelmann

First of all, before answering your question, thank you very much for receiving us by Zoom in the beautiful Maison Française that I have known now for half a century, and which you manage with great tact and energy. Special thanks to Kelly and Alice for organizing and holding this meeting with passion and vigilance. Thank you to all those who have spoken these last three hours. Your words, discussing and carrying my research forward, fill me with great emotion and gratitude. This has been a true experience of "thinking with” which sadly lacks in the anthropological acceleration imposed by today’s digital age and even more so by the pandemic.

I would like to thank the authors of the two books that bring us together today.

The extraordinary intelligence, precision and perseverance of Sara Gay Beardsworth, editor of the prestigious Library of Living Philosophers series, and of this volume of over 800 pages, in which thirty-six authors participated: philosophers, linguists, sociologists, anthropologists, without forgetting some eminent figures in the arts and letters, and politics as well.Your contributions, dear friends, your thoughts, praise or criticism, honor me, intimidate me and compel me. I am proud to be part of the prestigious Library of Living Philosophers series established in 1939, alongside the great names of philosophy who’ve inspired contemporary philosophical research: and especially to join the coterie of French philosophers honored by this series, namely Sartre, Ricoeur and Gabriel Marcel, being myself, now, one of the few women on the list.

At The Risk of Thinking by Alice Jardine, that patient and vigilant intellectual biography you dedicated to me, dear Alice, published by Bloomsbury Press, in which you invite me revisit, with great finesse and lucidity, my life and my research, my loves and my experience of motherhood. We have known each other since I began teaching at Columbia University’s Department of French and Romance Languages where you were my first American assistant. At the time professors Michael Rifleterre and Léon Roudiez headed the prestigious department, and of course, there was the faithful, unwavering presence of Columbia University Press, now run by Jenifer Crew, along with Lary Kritzman and his European perspective collection. It is thanks to them that my writing has been translated into English, and hence, become internationally accessible, which has made it possible for us to meet today. I can think of no better way to thank you, dear Alice, than to reveal the intimate side of our friendship to our friends here present, namely how you taught David Joyaux, my son with Philippe Sollers, how to sing "twinkle twinkle little star" the semester I was a permanent visiting professor at Columbia. He remembers it still. Today your book ends with a poem by David called “L’Ecriture."

*

Let me come back to your question, dear François. I very much enjoyed reading your latest book Un tout autre Sartre (Gallimard, 2020), I very much enjoyed your Pensée avec les oreilles et les airs de famille: une philosophie des affinités, as well as Le toucher des philosophes: Sartre, Nietzsche et Barthes au piano. You have generously welcomed me to France Culture. We have often crossed paths at bookstores at the launch of our books, and I can say that no matter how different our trajectories may be, we are bound by an authentic “affinity," and this Zoom is a further confirmation of that.

I am not a certified professional philosopher. I still keep my student notebooks in French philology at the University of Sofia, into which I studiously copied pages upon pages from Voltaire’s Dictionnaire Philosophique, from Diderot's Jacques le Fatalisteand Le Neveu de Rameau and from La Nouvelle Héloïse, Le Contrat Social and Confessions by Rousseau. The French Enlightenment taught me that philosophy is inseparable from this unveiling of language and imagination we call “literature.” The “dialectical materialism” that we were taught did not stop with Marx’s Capital and Lenin's Philosophical Notebooks; I also read Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit and continued to deepen my knowledge of his work in writing my thesis, Revolution in Poetic Language, which highlights a phrase from Phenomenology of Spirit: “What, therefore, is important in the study of Science, is that one should take on oneself the strenuous effort of the Notion.” Psychoanalysis was to teach me that "the strenuous effort of the Notion" is carried by the conscious and unconscious psycho-sexual investment.

I discovered Husserl in France; my Revolution in Poetic Language bears witness to this, and I discuss him as I develop my notions of the “semiotic” versus the “symbolic.” Marian Hobson examines this in the study she devotes to my research in the LLP volume.

I didn't know Freud; while rummaging through the family library, my sister discovered that my father had hidden at the very top, in the last row of the last shelf, up against the wall, the Bulgarian translation of Freud’s 1917 The Introduction to Psychoanalysis, translated into Bulgarian in 1947. Reading it was at the risk of becoming an enemy of the People! I discovered Freud from Lacan's seminars, led there by Philippe Sollers. It was also Sollers who got me to read Nietzsche.

This path was to lead me necessarily to the dismantling of ontotheology, at first closer to the transvaluation of values (Umwertung aller Werte) according to Nietzsche, and above all in the wake of post-war Heidegger to what he calls Verwinudung — which translates as “winning back,” or even “getting over.”

Attentive to Freud's "free association" and “transference," but also to literature, the interpretation I am trying to construct is not an “hermeneutic.” I seek to make "inner experience" heard in the sense of Georges Batailles, that is to say, as an "appropriation of life until death,” a “resisting withdrawal into oneself,” “identities,” and “limits." Could this be what the Jewish Kabbalah calls Techouva, the winning back or refounding of being?

The spawning (Bahnung in German) of thought thus understood is inseparable from writing in the sense that it absorbs the imaginary and implies transference. My neologisms (intertextuality, abjection, reliance, etc.) do not "subtitle" the "abstractions" that pre-exist them. I try to invite those I address to participate in the gestation of the idea, through what I call the flesh of words: drives, affects, sensations, emotions.

My early theoretical writings were more speculative. Following my own psycho-sexual maturation, and with psychoanalysis, my way of thinking now cohabits more explicitly with literary writing: academic exposition gives way to the essay, while psychoanalytical theorizing is supported by clinical vignettes where the words of the analysand and the analyst neither judge nor calculate but merely transform (as does the dream in Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams).

What do you call "phallic writing"? One that legislates, orders, sanctions, a kind of pure "symbolic" guaranteeing structure and truth? Writing as experience, a winning back, techouva, or refoundation is, to say the least, bisexual, at once structuring and polyphonic, a crossing of borders. The feminine of the man and the feminine of the woman participate and reveal themselves in it, but subordinated to a single refounding objective: singularity. In the sense Dun Scot (1266–1308) brought to light and which Hannah Arendt discovered in Heidegger's seminar. Singularity or Ecceitas: this man here, that woman there. In this regard, I would like to quote the conclusion from my trilogy Female Genius: "Each subject invents in his intimacy a specific sex,” let us call it singular. Thought or thinking, when it exists, makes this particularity, this singularity shareable.

*

F.N.: Looking back on your work, we are very impressed by your power of

thought. You have, in every theoretical field, in every kind of writing,

invested maximum intensity: you go all the way, methodically, whether in

language theory, in psychoanalytical interpretation, in the biographical

understanding of a personality or a work of art... What libido sustains your

endless desire to think, write and communicate? What is your engine, your fuel?

Secondary question: what determines your choice to write a theoretical essay or rather a novel?

J.K.: Maybe the fact that I don't recognize myself in this Kristeva you have just sketched in generous lines. I don't see myself in the image or the phenomenon because I travel within myself. But you can rephrase your question: why do you travel within yourself?

The "evidence based medicine,” which explains everything by "big data" would perhaps find that I have a "highly sensitive brain"? Freudian psychoanalysts will look toward the intensity of the drives and the capacity for sublimation, thanks to a successful Oedipus, with the double integration of paternal and maternal poles. Indeed, the two books that bring us together today, my biography in conversation with Samuel Dock and the biography by Alice Jardine, mention these interminable family discussions, in which I fought my father's orthodox faith armed with my mother's Darwinism. My father was angry, but he also maintained that books are the only value; and that there is no other way to "emerge from the bowels of Hell" (a quote from the Gospels, he claimed, referring to our native Bulgaria) than to learn foreign languages. Communist education was severe, but solid, and I was lucky enough to be a teenager during the thaw, that is, de-Stalinization. Another good fortune: France, which welcomed me with a scholarship, was open to foreigner students and I didn’t experience any prejudice — be it xenophobic or antifeminist — at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes, the University or at Saint Germain des Prés where I joined Philippe Sollers and the Tel-Quel group. This hospitality has not spared me the rubs of French nationalism: my book Etrangers à nous même bears witness to my experience of the Foreigner (L’Etrangère is the title of the now famous article Barthes wrote about me). But I am convinced an Enlightenment spirit deeply inhabits the thinking of the French. And I am betting on this perpetual political debate which, all things considered, leaves room for the foreigner that I am and that I will remain. The proof: this Zoom is impossible in France; it is hosted at the Maison Française of ..... New York. Proof, if any, that I am deeply cosmopolitan: "I travel within myself,” but with you. In the context of the pandemic, I call myself a sur-vivor. Not in the morbid sense of the term, but in the sense of what Freud called "the eternal Eros,” ending his Civilisation and Its Discontents.

To

put it another way, this journey of mine, including exile, is supported by an eroticization

of thought. Dare I say that thought thus understood as the flesh of words is a part of my sexual organs?

The novels? A nocturnal variation of thought bypass — what I call a-pensée: a way of bypassing binary thinking. Metaphysical, theoretical, psychoanalytical preoccupations fade in the face of the dreamlike, hallucinatory influx of scenes-sensations-emotions. The narrative resorbs the concepts that are never very far away. After Les Samouraïs, I wrote a series of "metaphysical detective stories,” which take the gamble of detecting where radical evil — that is, killing and murder — comes from. In The Enchanted Clock, set in Versailles and in contemporary astrophysics, the main character is Time.

*

F.N.: You have moved around intellectually a lot, unlike thinkers who spend their whole lives on a single concept and write variations on it. You look like a migrant who moves through identities, thoughts and writings, even though we recognize your touch, the Kristeva’s touch. When you think back to the early years, the 1970's, marked by hyper theory, the Tel Quel years, which some people are violently rejecting today, how do you look at these beginnings? With nostalgia, irony, pride?

Secondary question: Even if it's much too early, do you care about your intellectual legacy?

J.K.: In the 1970s I laid the foundation for what I called Transvaluation and Refoundation or Winning Back. Like all advances that revolt against conformism and stereotypes, this research (theoretical or literary) is susceptible to take hermetic, jargonized forms or, on the contrary, to be enclosed in politically correct ideologies.

Nevertheless, the epistemological necessity of Transvaluation and Refoundation calls to us today as we face the collapse or radicalization of ideologies, and find our political systems reduced to statistic management and to “calculation thinking." The media’s on-going spectacle and digital technology, which at the same time flatten, standardize and fragment, reject this questioning thought; or rather, they ignore it. But the approach I am talking about nevertheless manages to break through the lock-down of thought, which is worsening in these times of pandemic.

I have had to innovate and deepen my conception of psychoanalysis to accompany the inner experience of my patients in pandemic suffering (whether the sessions be in-person or remote). The unspeakable "traumas" and even the "central phobic nucleus" can find a working through and revive the psychic space of the analysand. I’d like to refer you to my position in the debate held at the initiative of the IPA posted on my site under the title "Psychoanalysis is a struggle for life,” in discussion with Virginia Ungar and Dominique Scarfone.”

Are you speaking of my "intellectual legacy"? I don't have one, not really. I am drawing up a will for my son and my copyrights. But as far as my thinking is concerned, let's keep in the open, in the space of transvaluation and refoundation.

*

F.N.: Debates on feminism are again very active, and involve generational conflicts. Is your reflection, both psychoanalytical and feminist, revived by the current demands for new rights, or by the communitarian conflicts over a feminism considered too white, too Western?

Secondary question:

How do you analyze the increasing public interest in sexual transition? What does it reveal about gender representation? Is it a symptom of social change?

J.K.: Some of the authors of the LLP volume have echoed criticisms made concerning my interest in the philosophy of the Enlightenment, my attachment to Europe, or my supposedly “white” and “essentialist” “feminism.” I respond to these suspicions and attacks with a maximum of details and sincerity in the LLP book. I thus refer you to my opening of the 51st IPA congress held in London in June 2019, entitled "Prelude for an Ethics of the Feminine,” where I take on the impossible mission of defining the “feminine," saying that "the feminine is the Higgs boson of the unconscious:” that is to say, just as the Higgs boson is untraceable but indispensable to the existence of matter, so is the feminine to the existence of psychic life. And I develop why "the feminine is transformative.” While I was writing this text, Miglena Nikolchina ended her contribution to the LLP volume by arguing that "Kristeva is a thinker of change.” How am I a thinker of change?

I argue, along with Tocqueville and Arendt, that something happened in Europe and nowhere else: we cut ties to religious tradition. Not to deny it (although, alas, some people do, and I fight them on it); but to question identities and values, and in doing so, endorse the risks of freedom. Freedom for women, men, children, slaves, the oppressed, the disabled. Whatever these identities and values are, and wherever they come from, those of the East, of the West, those of the Bible, the Gospels, the Koran, Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, humanism, feminism, etc., without taboo. In this spirit, I do not accept that post-colonialism should become an angry face-to-face between executioners and victims, guilt and revenge. There is no remedy for the identity clashes that shake democracies — this binary war between women and men, whites and blacks, radicalized sovereign-isms on both sides, — without the slow and indispensable process of transvaluation and winning back of identities and values. We must undertake and continue this process without respite at school, at university, in the media, on social networks, in families, in associations, in politics...

Texts by Ed Casey, Robert Harvey, Alina Feld, Elaine Miller — to name just a few of the participants in this process — bear witness to this. I should add that my seminar The Need to Believe developed from my work with the staff at the Cochin Hospital’s Maison des Adolescents, where we deal with teen-agers brain-washed into jihad and others whose need to believe devastates them to the point of suicide, vandalism, anorexia... I recall this in response to those who accuse me of sharing some supposed French colonial obsession with Islam... Faced with political Islam France is not retrograde. France is ahead in its awareness of radicalization: of its roots and its challenges.

As for Europe, I am proud to be a part of it despite its weaknesses, even its possible disintegration: Europe is not yet done in, but without it, multilateralism risks tumbling into mayhem. And since one is never more European than when one laughs at Europe, I’ll refer you to Daniel Cohn-Bendit's text in the LLP volume. After a very serious analysis of my Europeanism, he points out, tongue-in-cheek, that we are both followers of the Europe of Football, of European football. And I’ll add another joke in a similar vein: Bulgarian semioticians invented a cosmopolitan soccer team — as are all soccer teams world-wide — in which I am the only woman. Next to Cristiano Ronaldo, Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and of course Thalès de Millet.

As for the sexual transition, you mentioned, dear François, two remarks. First, the problem is heterosexuality. Will the two sexes die, each on its own, as Alfred de Vigny wrote and Marcel Proust repeated? The second problem arising from this is that of the reconstituted family (which I develop in my study Metamorphosis of Parenthood SPP colloquium, 73rd CPLF colloquium, May 2013, which you can find on my site). Where has the father gone? I end with a metaphor by evoking Jackson Pollock's paintings which bear the title One (a reference to the unity of the creator, of the father), where there is no identifiable, representational "image" and any possibility of “unity” is pulverized in the “dripping." It is important to accompany each family project, adoption, filiation, with personalized attention on a case-by-case basis. As always? No, more than ever before.

*

F.N.: What does the US mean to you? From the beginning, you have been welcomed here like a rock star. Have you thought about moving here? What do you like about the US and what don't you like?

Secondary question: More generally, what surprises you today?

J.K: I have often thought about moving to the United States, or rather to Canada, since French is the language I live and think in. Especially in times when a sovereignist ideology has held sway in France. The language, and my family, in particular, irrevocably attach me to France and what I call its openness to the multiverse. However, the United States remains my horizon. I share Hannah Arendt's diagnosis about US: extraordinary political freedom, on the one hand; heavy social obstacle on the other. The result is the recent cracks in democracy, but also the resistance of legal foundations. Multilateralism needs both the economic and libertarian power of American democracy and its exemplary educational system. At the same time, by balancing the US alliance with Europe, we could negotiate with the appetites of the Chinese giant from a position of strength and address the immensity of its culture. Beyond politics and economics, I’m talking, more profoundly, about conceptions of the individual, the social bond, and the freedoms that the conflict of civilizations puts to test.

What surprises me?

The immeasurable destructiveness of the speaking beings that we are does not surprise the psychoanalyst. I know that we are destroying the planet and I am not surprised that the most panicked are preparing to plant skyscrapers on Mars. In the meantime, we'd better vaccinate all earthlings against Covid-19 and its cousins, who will surely show up.

What surprises me, in the sense that surprise is the wellspring of philosophy — and as far as I am concerned this arouses joy, grace and serenity — is the capacity of women and men to survive, to bounce back, to re-found themselves and to start anew. I plan to have inscribed on my tombstone, on the Ile de Ré, a phrase by Colette: “Rebirth has never been above my strength".

|

|

|

|

A Webinar hosted by

La Maison Française,

New York University

On the occasion of the publication of The Philosophy of Julia Kristeva, ed. Sara G. Beardsworth, in The Library of Living Philosophers, Open Court Publishing Company, 2020 and of At the Risk of Thinking: An Intellectual Biography of Julia Kristeva, by Alice Jardine, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

François Noudelmann : The fabulous book

dedicated to your work has been published in the series The Library of Living

Philosophers. When critics try to define you, they hesitate between

psychoanalyst, semiotician, writer, and philosopher. Of course, you are all of

these definitions and more, but could you say something about your

identification with, or relationship to, philosophy? Even if there is not a

single definition of philosophy, could you say what role it has played, through

major or minor philosophical references, in your thinking?

Secondary question: There are not many women in philosophy. Does being a

woman philosopher imply adopting a phallic writing?

Julia Kristeva : Cher

François Noudelmann, avant de répondre à

votre question, d’abord un grand merci de nous recevoir par Zoom dans cette

belle maison française que je connais depuis un demi-siècle déjà, et dont vous

exercez la direction avec beaucoup de tact et d’énergie. Merci à toutes celles

et à tous ceux qui sont intervenus depuis trois heures déjà, et dont je viens

de recevoir avec beaucoup d’émotion et de gratitude les paroles, discutant et

prolongeant ma recherche. Ce fut une véritable expérience de « pensée

avec », qui manque beaucoup à l’accélération anthropologique imposée

par le numérique et plus encore par la pandémie.

Je voudrais remercier

d’abord les auteures des deux livres qui nous réunissent aujourd’hui.

En premier lieu,

l’extraordinaire intelligence, précision et persévérance de Sara Gay

Beardsworth, éditrice du gros volume de plus de 800 pages, auquel ont participé

trente-six auteurs : philosophes, linguistes, sociologues, anthropologues,

sans oublier quelques imminentes figures des arts et des lettres, de la

politique aussi. Certains en direct, d’autre en podcast. Vos contributions,

chers amis, vos pensées, éloges ou critiques, m’honorent, m’intimident et

m’obligent. Et je suis fière de participer à cette prestigieuse série de la Library

of living philosophers établit en 1939. A côté des grands noms de la

philosophie, qui inspirent la recherche philosophique contemporaine : et

tout particulièrement dans le petit groupe des trois philosophes français qui

sont honorés par cette série, à savoir Sartre, Ricoeur et Gabriel Marcel, étant

moi-même, désormais, une des rares femmes de la liste.

Et le deuxième livre, At the risk of thinking d’Alice Jardine, cette patiente et vigilante intellectual

biography que tu m’as consacrée, chère Alice, publiée par Bloomsbury Press,

et dans laquelle tu me fais revisiter, avec beaucoup de finesse et de lucidité,

ma vie et ma recherche, mes amours et ma maternité. Nous nous sommes connues

depuis mes premiers enseignements au département de French and Romance

linguises de Columbia University. Tu étais ma première assistante

américaine, aux côtés des professeurs Michael Rifleterre et Léon Roudiez qui

dirigeaient le prestigieux département. Et déjà avec la présence fidèle, qui ne

s’est jamais démentie, de Columbia University Press avec Jenifer Crew qui la

dirige maintenant, et Lary Kritzman avec sa collection European perspective.

C’est grâce à eux que mon écriture est devenue accessible en anglais dans la

globalisation, rendant ainsi possible notre rencontre aujourd’hui. Je ne

pourrais te remercier mieux, chère Alice, qu’en révélant, à nos amis ici

présents, la face intime de notre amitié c’est-à-dire David Joyaux, le fils que

nous avons avec Philippe Sollers, et qui se souvient toujours que quand il

m’accompagnait bébé pendant mon semestre de permanant visiting professor à

Colombia, c’est toi qui lui a appris à chanter « twinkle twinkle little

star ». Et aujourd’hui ton livre se termine par un poème de David intitulé

« L’Ecriture ».

* *

*

Je reviens à votre

question cher François. Avant de lire votre dernier livre Un tout autre

Sartre (Gallimard, 2020), j’ai beaucoup aimé vos Pensée avec les

oreilles et les airs de famille : une philosophie des affinités, ainsi

que Le toucher des philosophes : Sartre, Nietzsche et Barthes au piano.

Vous m’avez généreusement accueillie à France Culture, nous avons échangé

fréquemment à la sortie de nos livres en librairie, et je peux dire que quelque

différent que soient nos chemins, c’est bien une authentique

« affinité » qui nous relie, ce Zoom en est une confirmation

supplémentaire.

Je repends votre

question. Je ne suis pas une philosophe professionnelle diplômée. Je garde

encore mes cahiers d’étudiante en philologie française à l’Université de Sofia,

recopiant studieusement des pages et des pages du Dictionnaire philosophique Voltaire, ou du Neveu de Rameau ou de Jacques le Fataliste de

Diderot, ou encore de La Nouvelle Héloïse, du Contrat Social ou

des Confessions de Rousseau. Les Lumières Françaises m’ont appris que la

philosophie est inséparable de ce dévoilement du langage et de l’imaginaire que

l’on appelle « littérature ». Le matérialisme dialectique que l’on

nous enseignait ne se contentait pas des Cahiers dialectique de Lénine,

je lisais aussi la Phénoménologie de Hegel et j’ai continué à

approfondir ma connaissance de Hegel en écrivant ma thèse sur La révolution

du langage poétique, qui porte en exergue une phrase de la Phénoménologie :

« Dans l’étude scientifique ce qui importe donc c’est de prendre

sur soi l’effort tendu de la conception »

[1]

. La

psychanalyse devait m’apprendre que « l’effort tendu de la

conception » est porté par l’investissement psycho-sexuel conscient et

inconscient.

J’ai découvert

Husserl en France, Les révolutions poétique du langage en témoigne, et

je le discute au fur et à mesure que j’élabore mes notions de sémiotique versus symbolique. Marian Hobson en parle dans l’étude qu’elle consacre

à ma recherche dans le volume LLP.

Je ne connaissais pas

Freud ; en fouillant dans la bibliothèque familiale, ma sœur à découvert

que mon père avait caché tout en haut, dans la dernière rangée du dernier

rayon, tout contre le mur, la traduction bulgare de L’introduction à la

psychanalyse de 1917, traduite en bulgare en 1947. Il ne fallait surtout

pas le lire, pour ne pas devenir ennemi du Peuple ! J’ai découvert Freud à

partir des séminaires de Lacan, auxquels n’avait amené Philippe Sollers. C’est

Sollers aussi qui m’a fait lire Nietzsche.

Ce parcours devait me

conduite nécessairement au démantèlement de l’ontothéologie, d’abord

plus proche de la transvaluation des valeurs (Umwertung aller Werte)

selon Nietzsche, et surtout dans le sillage du second Heidegger à ce qu’il

appelle Verwiudung – traduit en français par

« appropriation », voire « tournure ».

A l’écoute de

« l’association libre » et du « transfert » selon Freud,

mais aussi attentive à la littérature, - l’interprétation que j’essaie

de construire n’est pas une « herméneutique ». Je cherche à faire

entendre « l’expérience intérieure » au sens de Georges Batailles,

c’est-à-dire « appropriation de la vie jusqu’à la mort » et

« contestation du repli sur soi », des « identités », et

des « limites ». Serait-ce ce que la kabbale juive appelle Techouva,

le retournement de l’être ?

Le frayage (Bahuung en allemand) de la pensée ainsi comprise, est inséparable de l’écriture au sens où celle-ci absorbe l’imaginaire et implique le transfère.

Mes néologismes (intertextualité, abjection, reliance, etc…) ne viennent

pas « sous-titrer » des « abstractions » qui leur

préexistent. J’essaie d’inviter ceux ou celles à qui je m’adresse à participer

à la gestation de l’idée, en passant par ce que j’appelle la chair des

mots : pulsions, affects, sensations, émotions.

Mes premiers écrits

théoriques étaient plus spéculatifs. Suite à ma propre maturation psycho-sexuelle,

et avec la psychanalyse, ma manière de penser cohabite désormais plus

explicitement avec l’écriture littéraire : l’exposé académique cède la

place à l’essai ; tandis que la théorisation psychanalytique s’étaye sur

des vignettes cliniques où la parole de l’analysant et de l’analyste ni ne juge

ni ne calcule mais se contente de transformer (comme le fait le rêve selon

Freud dans L’interprétation des rêves).

Qu’est-ce qu’une

« écriture phallique » dites-vous ? Celle qui légifère, ordonne,

sanctionne, du pur « symbolique » garant de la structure et de

la vérité ? L’écriture comme expérience, tournure, techouva,

ou refondation est pour le moins bisexuelle, à la fois mise en ordre et

polyphonie, traversée des frontières. Le féminin de l’homme et le féminin de la

femme y participent et s’y révèlent, mais subordonnés à un seul objectif

refonder : la singularité. Au sens de Dun Scot (mort en 1308)

qu’Hannah Arendt a découvert dans le séminaire de Heidegger. Singularité ou Ecceitas : cet homme-ci, cette femme-là. Je voudrais citer la

conclusion à cet égard, de ma trilogie Le génie féminin :

« Chaque sujet invente dans son intimité un sexe spécifique », disons singulier. La pensée, quand elle existe, rend cette particularité, cette

singularité partageable.

* *

*

F.N. : Looking back on your

work, we are very impressed by your power of thought. You have, in every

theoretical field, in every kind of writing, invested maximum intensity: you go

all the way, methodically, whether in language theory, in psychoanalytical

interpretation, in the biographical understanding of a personality or a work of

art... What libido sustains your endless desire to think, write and

communicate? What is your engine, your fuel?

Secondary question: what determines your choice to write a theoretical

essay or rather a novel?

J.K. : Peut-être le fait que

je ne me reconnais pas dans cette Kristeva que vous venez de dessiner à grands

traits généreux. Je ne me retrouve pas dans l’image ou le phénomène, je me

voyage. Mais vous pouvez reformuler votre question : pourquoi vous

vous voyagez-vous ?

La « evidence

based medecine », qui explique tout par les « big data »,

trouvera peut-être que j’ai une « higth sensitive brain » ? Les

psychanalystes freudiens chercheront du coté de l’intensité des pulsions et des capacités de sublimation, grâce à un Œdipe réussi, avec double

intégration du pole paternel et du pole maternel. En effet, les deux livres qui

nous réunissent aujourd’hui, ma biographie en conversation avec Samuel Dock et

la biographie par Alice Jardine, mentionnent ces interminables discussions

familiales, où je combattais la foi orthodoxe de mon père en m’appuyant sur le

darwinisme de ma mère. Mon père se mettait en colère, mais il soutenait aussi

que les seules valeurs ce sont les livre ; et qu’il n’y a pas d’autre

moyen de « sortir des intestins de l’Enfer » (citation des Evangiles,

prétendait-il, désignant ainsi notre Bulgarie natale) que d’apprendre les

langues étrangères. L’éducation communiste était sévère, mais solide et j’avais

la chance d’être adolescente pendant la période du dégel, c’est-à-dire

la déstalinisation. Autre chance : la France qui m’a accueillie avec une

bourse d’étude n’était pas sursaturée d’étrangers et j’ai été reçue sans

préjugés – ni xénophobe, ni antiféministe – aussi bien à l’Ecole des Hautes

Etudes, qu’à l’Université de Paris VII Denis Diderot qui m’a ouvert ses portes

et où je suis devenue professeure, ou à Saint Germains des Prés, la revue

Tel-Quel de Philippe Sollers. Cette hospitalité ne m’a pas épargné les micros-signes

du nationalisme français, mon livre Etrangers à nous même témoigne de

l’expérience de l’Etrangère (c’est le titre de l’article désormais

célèbre que Barthes a écrit sur moi). Mais l’esprit universaliste habite

profondément la pensée du peuple français, j’en suis persuadée. Et je parie sur

ce perpétuel débat politique qui, tout compte fait, laisse de la place à

l’étrangère que je suis et que je resterais. La preuve : ce Zoom est

impossible en France, il est domicilié (hosted) à la Maison

Française, mais à …. New York. La preuve, s’il en est une, que je suis

profondément cosmopolite : « je me voyage ». Dans le contexte de

la pandémie, je dis que je suis une sur-vivante. Non pas au sens morbide

du terme, mais au sens de ce que Freud appelait : « l’éternel

Eros », en terminant son Malaise dans la civilisation.

Pour le dire

autrement, ce parcours, exil compris, s’appuie, s’étaye, sur une érotisation de la pensée. Oserai-je dire que la pensée ainsi comprise, avec la chair des

mots, fait partie de mes organes sexuels ?

Les romans ? Une

variation nocturne de l’a-pensée : je l’écris a-pensée. Les préoccupations

métaphysiques, théoriques, psychanalytiques s’estompent devant l’afflux

onirique, hallucinatoire de scènes-sensations-émotions. Et la narration,

le récit résorbe les concepts qui ne sont jamais très loin. Après Les

Samouraïs, j’ai écrit une série de « polars métaphysiques », qui

font le pari de savoir d’où vient le mal radical, c’est-à-dire la mise à mort,

le meurtre. Dans L’Horloge enchantée, qui se passe à Versailles et dans

l’astrophysique contemporaine, le personnage principal est le Temps.

* *

*

F.N. : You have moved around

intellectually a lot, unlike thinkers who spend their whole lives on a single

concept and write variations on it. You look like a migrant who moves through

identities, thoughts and writings, even though we recognize your touch, the

Kristeva’s touch. When you think back to the early years, the 1970's, marked by

hyper theory, the Tel Quel years, which some people are violently rejecting

today, how do you look at these beginnings? With nostalgia, irony, pride?

Secondary question: Even if it's much too early, do you care about your

intellectual legacy?

J.K. : Les années 70 sont

fondatrice de cette pensée que j’ai appelée Transvaluation et Retournement.

Comme toutes les avancées révoltées contre les conformismes et les stéréotypes,

ces recherches (théoriques ou littéraires) ont pu prendre des formes

hermétiques, jargonnantes ou, au contraire, être enfermées dans des idéologies politicaly

corrects.

Il m’empêche que la

nécessité épistémologique de la Transvaluations et du Retournement s’impose

aujourd’hui, face à l’écroulement ou à la radicalisation des idéologies, et

face au politique réduit à une gestion à coups de statistiques, à la

« pensée-calcul ». La médiatisation spectaculaire et le numérique,

qui à la fois aplanissent, standardisent et fragmentent, rejettent en effet

cette pensée questionnante ; ou plutôt, ils l’ignorent. Mais l’approche

dont je parle parvient néanmoins à percer le confinement de la pensée,

qui s’aggrave en temps de pandémie.

Et j’ai pu pour ma

part développer ma conception de la psychanalyse, qui s’innove et

s’approfondit, dans l’accompagnement de l’expérience intérieur en souffrance

pandémique, entre séances présentielles et distancielles. Les

« traumas » indicibles et jusqu’au « noyau phobique central »

peuvent trouver une perlaboration, et faire revivre l’espace psychique des

analysants. Je vous renvoie à mon site et à un débat qui s’est tenu à

l’initiative de l’IPA sous le titre « La psychanalyse est un combat pour

la vie, discussion avec Virginia Ungar et Dominique Scarfone ».

Vous me parlez de ma

« intellectual legacy » ? Je n’en ai pas, pas vraiment. Je fais

un testament pour mon fils et mes droits d’auteure. Mais concernant ma pensée,

restons dans l’ouvert, la transvaluation et le retournement.

* *

*

F.N. : Debates on feminism

are again very active, and involve generational conflicts. Is your reflection,

both psychoanalytical and feminist, revived by the current demands for new

rights, or by the communitarian conflicts over a feminism considered too white,

too Western?

Secondary question:

How do you analyze the increasing public interest in sexual transition?

What does it reveal about gender representation? Is it a symptom of social

change?

J.K. : Certains auteurs du

volume LLP ont fait échos à des critiques qu’on a pu formuler concernant mon

intérêt pour la philosophie des Lumières, mon attachement à l’Europe, ou encore

à mon « féminisme » qui serait « white » et « essentialiste ».

Je réponds à ces soupçons et attaques avec un maximum de détails et de

sincérité dans le livre LLP. Je vous renvoie ainsi à mon ouverture du 51

congrès de l’IPA qui s’est tenu à Londres en Juin 2019, et qui s’intitule

« Prélude pour une éthique du féminins », où j’assume la mission

impossible de définir le « féminin », en disant que « le

féminin est le boson de Higgs de l’inconscient » : c’est-à-dire

introuvable mais indispensable à l’existence de la matière, en l’occurrence

indispensable à l’existence de la vie psychique. Et je développe pourquoi

« le féminin est transformatif ». Pendant que j’écrivais ce texte,

Miglena Nikolchina achevait sa contribution au volume LLP en argumentant que

« Kristeva is a thinker of change ». Comment ?

Je soutiens, avec

Tocqueville et Arendt, qu’un événement s’est produit en Europe et nulle part

ailleurs : on a rompu le fil avec la tradition religieuse. Non pour la

dénier (bien qu’hélas certains pratiquent ce déni, et je les combats) ;

mais pour questionner les identités et les valeurs aux risques

de la liberté. Liberté des femmes, des hommes, des enfants, des

esclaves, des opprimés, des sexes, des handicapées. Quelles que soient ces identités et ces valeurs, et d’où qu’elles viennent, celles de l’Est, de l’Ouest,

celles de la Bible, des Evangiles, du Coran, du Taoïsme, du Confucianisme, du

Bouddhisme, de l’humanisme, du féminisme, etc… sans tabou. Dans cet esprit, je

n’accepte pas que le post-colonialisme se crispe en un face-à-face coléreux

entre bourreaux et victime, culpabilité et revanche. Il n’y a pas d’autre

remède aux heurts identitaires qui secouent les démocraties, à cette guerre

binaire entre femmes et hommes, blancs et noirs, souverainismes radicalisés de

part et d’autre, – sans le lent et indispensable processus de transvaluation et

de retournement des identités et des valeurs dont je me réclame.

A entreprendre et continuer sans relâche à l’école, à l’université, dans les

médias, sur les réseaux sociaux, dans familles, les associations, les Etats…

Les textes de Ed

Casey, Robert Harvey, Alina Feld, Elène Miller – pour ne citer que quelques-uns

des participants de ce processus, et toutes les interventions depuis tris

heures aujourd’hui (Cécilia, Marian, Fanny, Rachel, Noëlle, Eva, Emilia) - en

témoignent. J’ajoute que mon séminaire Le besoin de Croire travaille

avec des collègues psychanalystes et le personnel soignant de la maison des

adolescents de l’hôpital Cochin, où nous recevons des adolescents candidat au

Djihad. Mais aussi d’autres dont le besoin de croire dévasté les conduit

au suicide, au vandalisme, à l’anorexie… Je rappelle ceci en réponse à ceux qui

m’accuse de partager je ne sais qu’elle obsession coloniale française par

l’Islam… Face à l’Islam politique la France n’est pas rétrograde, la France est

en avance dans la prise de conscience de la radicalisation : de ses

racines et de ses défis.

Quant à l’Europe, je

suis fière d’en être malgré ses faiblesse, voir son délitement possible :

l’Europe n’est pas encore K.O., mais sans elle le multilatéralisme risque de

tomber dans le chaos. Et puisque on n’est jamais plus Européen que quand

on rit de l’Europe, je vous renvoie au texte de Daniel Cohn-Bendit dans le

volume LLP. Après une analyse très sérieuse sur mon européanisme, il s’appuie,

en souriant, sur le fait que nous sommes tous deux adeptes de l’Europe du

foot : du foot européen, du soccer. Et j’ajoute une autre blague

dans le même esprit : les sémioticiens bulgares on inventé une équipe de

foot cosmopolite, comme le sont toutes les équipes de soccer au monde, dans

laquelle je suis la seule femme. A côté de Cristiano Ronaldo, Thomas Sebeok,

Umberto Eco et bien sûr Thalès de Millet.

Quant à la transition

sexuelle, que vous rappelez cher François, deux remarques. D’abord, le problème

c’est l’hétéro-sexualité. Les deux sexes mourront-ils chacun de leur

côté, comme l’écrivait Alfred de Vigny repris par Marcel Proust ? Et en

même temps, le deuxième problème qui en découle, celui de la famille recomposée

(que je développe dans mon étude les Métamorphose de la parentalité,

colloque SPP, 73ème colloque CPLF, mai 2013, que vous pouvez trouver

sur mon site). Où est passé le père ? Je finis par une métaphore en

évoquant les tableaux de Jackson Pollock qui portent le titre One (un

renvoyant à l’unité du créateur, du père) tandis qu’il n’y pas

« d’image » identifiant une représentation : donc toutes

« unité » est pulvérisée dans le « dripping ». Il importe

d’accompagner chaque projet de famille, adoption, filiation, par une attention

personnalisée au cas par cas. Comme

toujours ? Non, plus que jamais.

* *

*

F.N. : What does the US mean

to you? From the beginning, you have been welcomed here like a rock star. Have

you thought about moving here? What do you like about the US and what don't you

like?

Secondary question: More generally, what surprises you today?

J.K. : J’ai souvent pensée à

m’installer au Etats-Unis, ou plutôt facilement au Canada, le français étant la

langue dans laquelle je vis et je pense. Surtout en période de poussée

souverainiste en France. La langue, et surtout la famille, m’attachent

définitivement à la France, à son autre face que j’appelle son ouverture

au multivers. Pourtant, ce sont les Etats-Unis qui demeurent mon

horizon. Je partage le diagnostic de Hannah Arendt : extraordinaire

liberté politique, d’une part ; lourde pesanteur sociale de l’autre. Il en

résulte les récents craquements de la démocratie, mais aussi la résistance des

fondations juridiques. Le multilatéralisme a besoin de la puissance économique

et libertaire de la démocratie américaine, et de son système éducatif

exemplaire. En équilibrant l’alliance des Etats-Unis avec l’Europe, nous

pourrions négocier en position de force les appétits du géant Chinois et

aborder l’immensité de sa culture. Je ne parle pas seulement des domaines

politique et économique, mais plus profondément des conceptions de la personne,

du lien social, et des libertés que le conflit des civilisations met à

l’épreuve.

Qu’est-ce qui me

surprend ?

L’incommensurable

destructivité des êtres parlant que nous sommes ne surprend pas la psychanalyste.

Je sais que nous sommes en train de détruire la planète et je ne m’étonne pas

que les plus paniqués se préparent à planter des gratte-ciels sur Mars. En

attendant on ferait mieux de vacciner tous les terriens contre la Covid-19 et

ses cousins, qui ne manqueront pas de se manifester.

Ce qui me surprend,

au sens où la surprise est à l’origine de la philosophie, et en ce qui me

concerne elle suscite joie, grâce et sérénité, c’est la capacité des femmes et

des hommes à survivre, à rebondir, à se refonder et à re-commencer.

J’inscrirais sur ma tombe, à l’Ile de Ré, une phrase de Colette :

« Renaitre n’a jamais été au-dessus de mes forces ».

[1] Hegel Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, La phénoménologie de l’esprit I, trad. Jean Hyppolite, Paris, France, Aubier-Montaigne, 1947, p. 54.