|

|

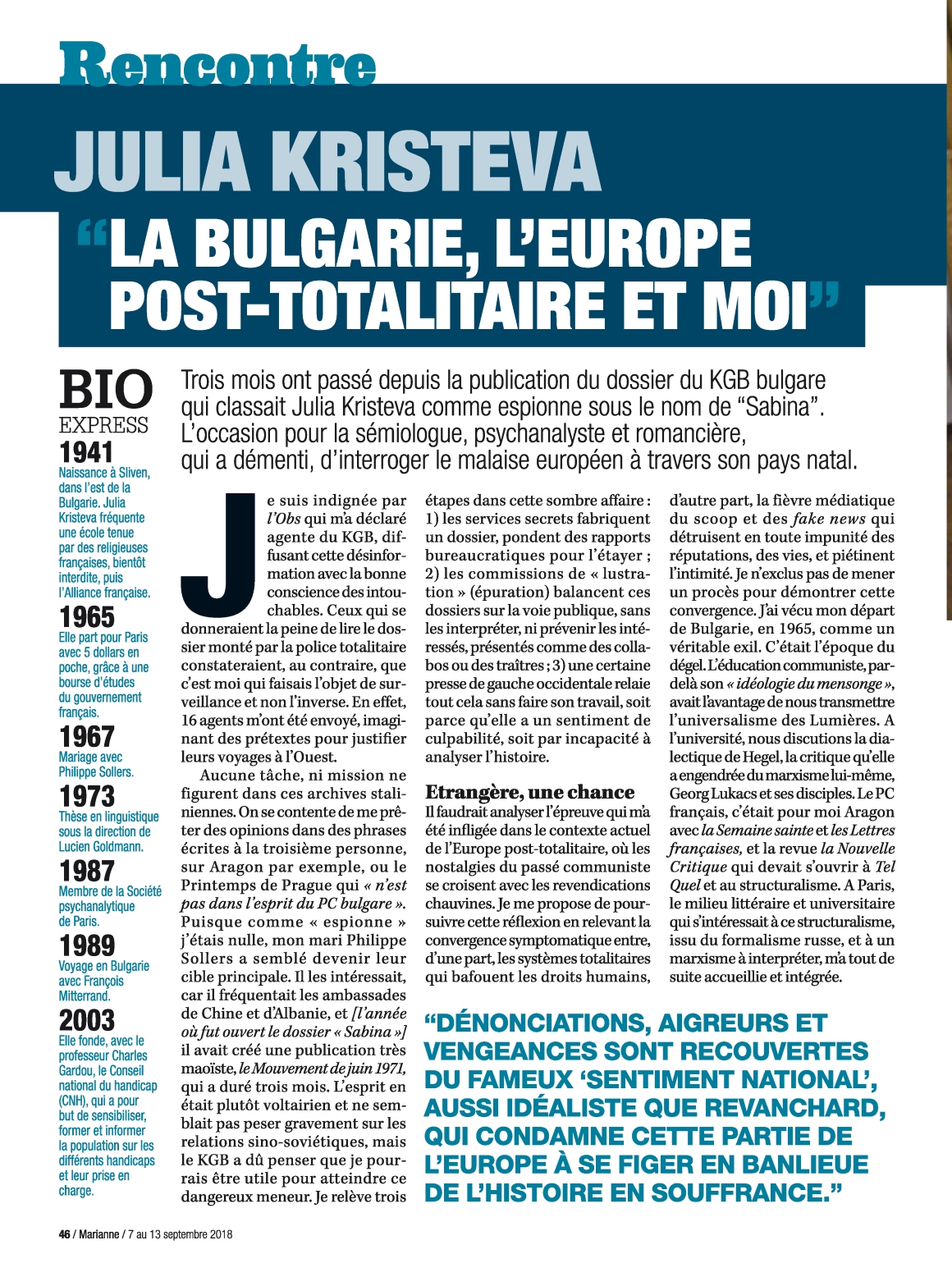

Bulgaria,

Post-Totalitarian Europe, And Me

It’s been three months

since the publication, via Sofia, of the Bulgarian communist

I

am indignant that Le

Nouvel Observateur, the

French weekly, openly declared me a KGB agent, spreading this falsehood with

the impunity of those who think they are not accountable to anyone. Had the journalists taken the trouble to read

the dossier fabricated by the totalitarian police, they would have found clear

evidence that I was the one subjected to surveillance, not the other way

around. Several journalists in Bulgaria in fact did just this (1), declaring the dossier empty and fit only to be thrown in the

trash, along with the tendentious Commission as well. Indeed some sixteen agents were sent my way

in order to contact just one “spy. ” They came up with imaginary pretexts to

justify their trips to the West. My

husband, Philippe Sollers, who distrusted pro-Soviet regimes, set his foot down

against our receiving any Bulgarian visitors. He adamantly refused to see them. That we dined with this apparatchik

who claims he “recruited” me is totally implausible.

Revealingly,

there are no informant missions assigned to me in these Stalinist archives.

Whoever devised them merely attributed opinions to me expressed in the 3rd

person, for example on Aragon or on the “Prague Spring” as being “not in the

spirit of the Bulgarian Communist Party…” Because I made such a lousy “spy,” Sollers seemed to become their

primary target. He was of interest to

them because he spent time at the Chinese and Albanian embassies, and (the year

the “Sabina” dossier got underway), founded the Maoist publication, Le Mouvement de juin 1971 ; it lasted three months

and was Voltaire-like in spirit. One could hardly say it weighed heavily on

Sino-Soviet relations! But the secret agents must have thought I’d be useful in

getting to this “dangerous” leader.

Allow

me to highlight the three stages of this dark business : 1/ The Secret Services create

a dossier, filling it with bureaucratic reports to give it weight ; 2/ The

« Lustration » (purging) Commission, in charge of the secret police

archives, tosses these dossiers to the public without analysing them, without

warning those they’ve accused of being It

is important to situate and analyse the ordeal that was inflicted upon me in

the larger, current context of post-totalitarian Europe where nostalgia for

communism gets entangled with

I

experienced my departure from Bulgaria in 1965, with a scholarship from the

French government, as an exile. It was

the era of the thaw. Communist

education, beyond its “lying ideology” which Soljenitsyne decried as more

pernicious than restrictions on freedom, did nevertheless convey the

universalism of the Enlightenment. At

university we discussed Hegel’s dialectic, the critique it produced of

Marxism, Georg Luckas and his

disciples. The French Communist Party

was, for me, Aragon with his La Semaine sainte and Les Lettres françaises, and also the review, La

I

enrolled at the École des Hautes Études and took Lucien Goldmann’s seminar.

I

therefore cut ties with Bulgaria (this was easy in an era without the Internet

or phones) but obviously not with my family—who came to France three times

between 1966 and 1989 thanks to the intervention of Jacques Chaban-Delmas

(contacted by my in-laws in Bordeaux)—and with whom I corresponded by

mail. It was this correspondence of 29

letters that was intercepted and divulged in the Bulgarian dossier. This is

what I find to be the most sordid part of this whole affair—a total violation

of my privacy. At the very moment when the world is troubled by the fact that

personal information is being exposed without permission via social media, my

letters have been diffused, not only in the Bulgarian KGB archives, but

throughout the entire world and not a single journalist was troubled by that.

The Commission in Sofia wasn’t troubled either.

It

was imperative not to be considered an “enemy of the people” in Bulgaria

because my parents and my sister lived there. I tried to keep up good relations by going periodically to the embassy,

eventually to get their visas. I

inevitably had to deal with the

apparatchiks sitting behind desks, most of whose names I didn’t know, and can’t

remember. I had kept some contact with

the dissident movement and knew it had come upon hard times. I didn’t return to Bulgaria for a very long

time.

I

finally did return in 1983 with my son (born 1975) so that he could meet my

parents. I went back again in January

1989 with François Mitterrand who invited me to join his delegation; we met

with dissidents such as the future president of the Republic of Bulgaria, Jeliu

Jeliev, and my friend Blaga Dimitrova, future vice-president. My father passed

away in September of the same year, in strange circumstances: it seemed “they”

were doing experiments on the elderly and he was cremated against his

will. Graves, you see, were reserved for

communists only, but if I could just die before him, my notoriety would

guarantee us this privilege (of being together in the same grave)! I had the impression a kind of street gang

logic ruled the country; the lines were incredibly long everywhere, people

spoke differently. In the twenty-five

years I had been away, my mother tongue had become brutal, people spoke in a

volley of insults.

With

the fall of the Berlin Wall, I started going there more regularly. I returned in 2002 when my mother died and

when the University of Sophia granted me the title of Docteur Honoris

Causa. In 2014, the University of Sofia

organised a colloquium on my work. There

I met with a young generation of philosophers, sociologists and analysts

intellectually engaged in a demanding, thoughtful way by the political and

ethical debates in Europe and the United States. They were both anxious and

lucid about the challenges facing Bulgaria with its political imbroglios. Numerous voices, both known and unknown,

spoke out to denounce the deleterious climate created by the procrastinations

of the so-called “Commission ». With a troubled Europe as backdrop, these reactions show that diverse

currents still run through opinion in

the public sphere there.

Some

reclaim communist dogma and turn towards Russia—bulwark and Big Brother. Others continue to count on European aid,

with and despite of how funds inevitably drift toward the Mafia. Still others, rare but tenacious, are hoping

for the democratic reforms favored by the European Union. But during this economic and political

stalemate, the ghosts of totalitarianism do not stay hidden away in the police

filing cabinets. Those ghosts are

invading and filling the public square with resentment. My take on this is Nietzschean : I see

it as an incapacity to transform past wounds and current frustrations into

actions. Instead, we see a collective

wallowing in reactionary hostility. People cloak their bitterness, vengeance, and denunciations in that

notorious “national sentiment,” which is both idealistic and

spiteful—condemning this part of Europe to freeze in the suburbs of history,

suffering. Just as with these so-called

“purges of the past », validating Stalinist methods by taking them up again

and failing to question police proceedings—and without interviewing those who

are being slandered. And all of this happens in such a way that the dogmatic

regime of the past is relayed forward to the present by the new regime of the

« buzz » and a form of thinking based only in calculus. Have we

really forgotten the Stalin Show Trials?

The

only way out of this toxic state is to deepen our understanding of

totalitarianism by probing its different facets, its institutional history, and

its cultural memory. In writing Bulgaria, My Suffering (1994), I tried not

to forget to emphasize religious roots as well.

The

Orthodox faith has magnificent moments, notably its understanding of pain and

grief, with rituals that offer a sensorial celebration. But it does not allow for any real reflection

on personal freedom. It lacks the

Renaissance’s hymn to liberty and its risks. Bulgaria went through a kind of precocious Renaissance in the tenth

century when Christianity spread among a people without a firmly implanted

national identity; yet by devising the Cyrillic alphabet, this people created

and safeguarded its culture. Cyrillic

worked like a powerful anti-depressant, capable of welding together a nation.

On

the other hand, in Bulgaria, as in other countries, especially in Eastern

Europe, Enlightenment ideals were imposed by an elite and did not sufficiently

integrate themselves into social behaviour and institutions. Though humanist thinking and questioning

flourished in universities, it was absent in the political sphere. Upon this bedrock, communism grafted its

ideals, but wayward totalitarianism trampled social and societal aspirations,

turning citizens away from their citizenship. Post-communism is today tempted by a return to spirituality, whether

reactionary or communist religious faith—one which moves alongside our

spectacle-oriented, hyperconnected, marketing-driven society without

questionning it. More drastically than in other European countries,

post-totalitarian democracies are confronted with the difficulty of bringing to

life a humanist culture whose refoundation, ever in progress, requires the

continual questionning of identity, nation, faith, and the need to believe itself.

Europe

carries a heavy responsibility within this deepening fracture that is crippling

its overarching project. If the

accomplishment of human rights for all means guaranteeing respect for the

person and his or her creative singularity, the movement of capital is not a

sufficient guarantee these rights will be upheld. Education, professional

training, and culture must be our focus, in our schools and in our

businesses. Only in this way can we

foster the much needed re-evaluation of the past so that reactive resentments

can give way to political and democratic renewal.

The

only way we can save ourselves is by exercising constant

vigilance that it is the human being who

is at the center of the media-sphere where we are all such consumed actors.

Bulgaria, my suffering…

Julia Kristeva

|

|

|---|