|

||

|

|

|

|

Marianne du 7 septembre 2018

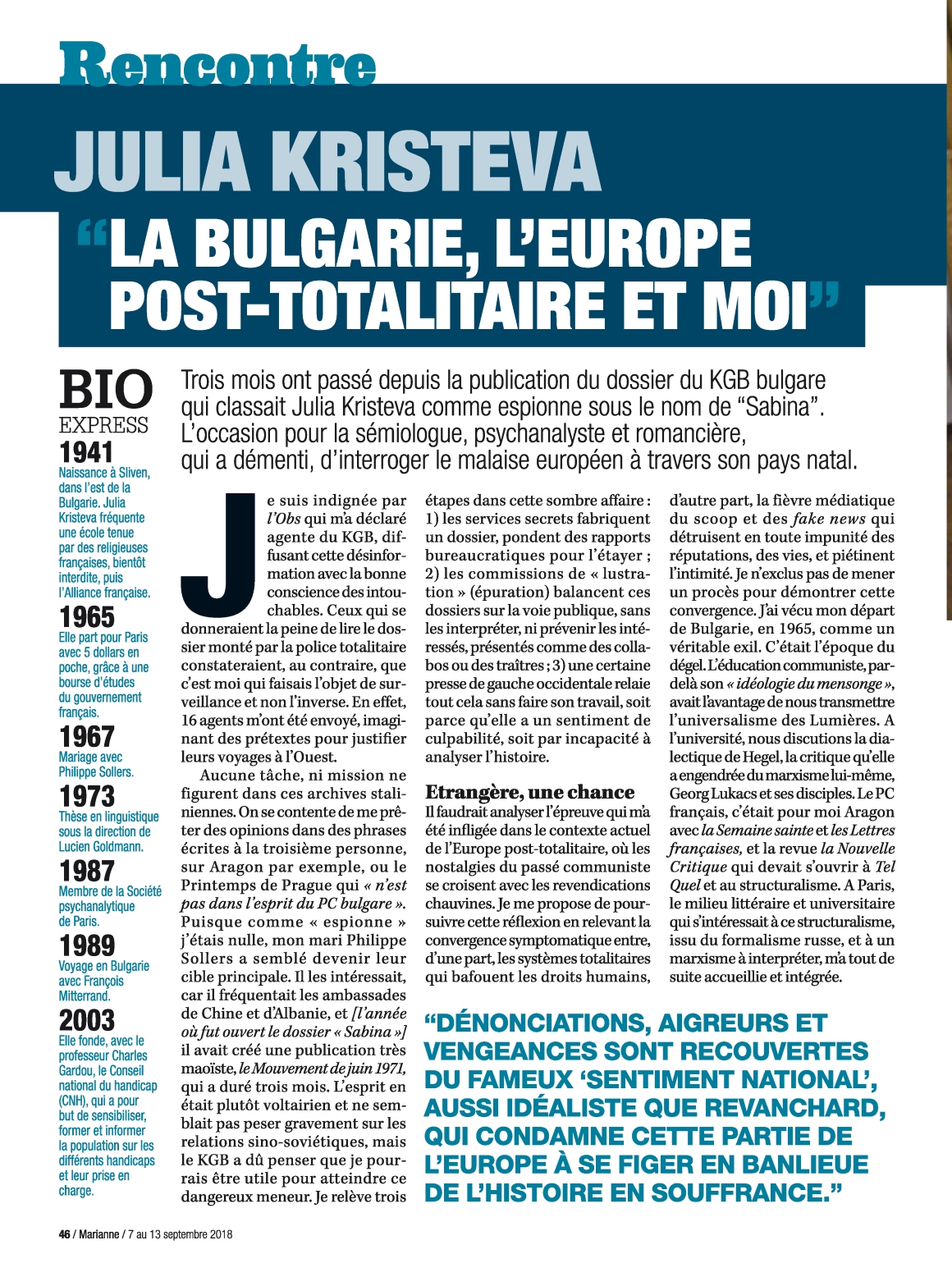

Julia Kristeva : La Bulgarie, l'Europe post-totalitaire et moi

Trois mois ont passé

depuis la publication, par Sofia, du dossier de la police secrète

communiste bulgare, qui classait Julia Kristeva comme espionne sous le nom

de «Sabina». L’occasion, pour la sémiologue psychanalyste et romancière,

qui a fermement démenti, d'interroger le malaise européen, à travers sa

Bulgarie natale.

Je suis indignée par l'Obs qui m'a déclarée agente du KGB,

diffusant cette diffamation et cette désinformation avec la bonne

conscience des intouchables. Les journalistes qui se donneraient la

peine de lire le dossier monté par la police totalitaire

constateraient, au contraire, l'évidence que c'est moi qui faisais

l'objet de surveillance et non l'inverse. Certains l'ont fait, en

Bulgarie même (cf. ici), renvoyant

« à la poubelle » le dossier vide et la Commission tendancieuse.

En effet, seize agents m'ont été envoyés pour une « espionne ». Ils ont imaginé des

prétextes pour justifier leurs voyages à l'Ouest. Philippe Sollers, mon

mari, qui se méfiait beaucoup des régimes prosoviétiques, avait mis son

veto sur les éventuels solliciteurs et visiteurs bulgares. Il a

toujours refusé de les voir. Invraisemblable, que nous ayons dîné avec

cet apparatchik qui prétend m'avoir « recrutée » à cette

occasion.

Aucune tâche de renseignement, aucune mission d'enquête qui

m'auraient été assignées ne figurent dans ces archives staliniennes. On

se contente de me prêter des opinions dans des phrases écrites à la 3e

personne, sur Aragon par exemple, ou le « printemps de

Prague » qui « n'est pas dans l'esprit du PC bulgare »

... Puisque comme « espionne » j'étais nulle, Sollers a

semblé devenir leur cible principale. Il les intéressait car il

fréquentait les ambassades de Chine et d'Albanie, et (l'année où fut

ouvert le dossier « Sabina ») il avait créé une publication très

maoïste, Le Mouvement de juin 1971, qui a

duré trois mois. L'esprit en était plutôt voltairien et ne semblait pas

peser gravement (!) sur les relations sino-soviétiques, mais les agents

secrets ont dû penser que je pourrais être utile pour atteindre ce

dangereux meneur.

Je relève trois étapes dans cette sombre affaire : 1/ les

services secrets fabriquent un dossier, pondent des rapports

bureaucratiques pour l'étayer ; 2/ Les commissions de

« lustration » (épuration), chargées des archives de la

police secrète, balancent ces dossiers sur la voie publique, sans les

interpréter, ni prévenir les intéressés, présentés comme des collabos

ou des traîtres ; 3/ Une certaine presse de gauche occidentale

relaie tout cela sans faire son travail, soit parce qu’elle a elle-même

un sentiment de culpabilité, soit par incapacité à analyser l’histoire.

Il faudrait situer et analyser l'épreuve qui m'a été infligée dans

le contexte actuel de l'Europe post-totalitaire, où les nostalgies du

passé communiste se croisent avec les revendications chauvines, et

mettent à mal la viabilité de l'Union européenne. Je me propose de

poursuivre cette réflexion ailleurs, en me bornant aujourd’hui de

relever la convergence symptomatique entre, d'une part, les systèmes

totalitaires qui bafouent les droits de l'homme et de la femme et,

d'autre part, la fièvre médiatique du « scoop » et des « fake news » qui

détruisent en toute impunité des réputations, des vies, et piétinent

l'intimité. Et je n'exclus pas de mener un

procès pour démontrer cette convergence. Mais une réflexion s'impose,

sur toutes les composantes de ce symptôme, quand les débris du

communisme poussent derrière les mouvements nationalistes en Europe de

l'Est et pas seulement, et quand le « quatrième pouvoir »

médiatique perd son indépendance dans les écueils de la démocratie

interconnectée.

J’ai vécu mon départ de Bulgarie (en 1965 avec une bourse d’études

du gouvernement français, ndlr) comme un véritable exil. C’était

l’époque du dégel. L’éducation communiste, par-delà son

« idéologie du mensonge » dont Soljenitsyne disait qu'elle

était plus pernicieuse que les privations affichées de liberté, avait

l'avantage de nous transmettre l'universalisme des Lumières. A

l'université, nous discutions la dialectique de Hegel, la critique

qu'elle a engendrée du marxisme lui-même, Georg Luckas et ses

disciples. Le PC français c’était pour moi Aragon avec La Semaine sainte et Les Lettres françaises, et la revue La Nouvelle Critique qui devait s'ouvrir à Tel Quel et au structuralisme. À Paris, le milieu littéraire et

universitaire qui s’intéressait à ce structuralisme, issu du formalisme

russe, et à un marxisme à interpréter, m'a tout de suite accueillie et

intégrée. Je voyais que la France sortait de la guerre d'Algérie,

coincée et coupable, et aussi jamais plus française qu'en retrouvant sa

mémoire corrosive dans les mouvements les plus audacieux de la pensée

européenne.

Je me suis inscrite à l’École des Hautes Études au séminaire de

Lucien Goldmann qui réinventait Marx avec Pascal, Hegel et le

structuralisme, et en même temps à celui de Roland Barthes qui faisait

de la littérature à travers le « nouveau roman » et la

sémiologie. J’étais heureuse d'appartenir à un monde nomade – étudiants

allemands, italiens, anglais, latino-américains, exceptionnellement de

l'Est européen –, qui, dans l'esprit qui précédait 1968, constituait

une communauté internationale et chercheuse. Mon étrangeté m’a paru une

chance, même si j'ai d'emblée su que je ne serais jamais française parmi les Français. C'était un

état d’apesanteur, certes douloureux, mais ouvert à la quête, à l'innovation. Mon inquiétude politique, mes

contacts avec les dissidents de l'Est européen m'ont rendue plutôt

critique envers les militants. Ma « dissidence », mon « engagement » fut de saisir la liberté intellectuelle qui s'offrait à moi pour

développer les savoirs que j'apportais de Bulgarie et que j'ai pu

approfondir au contact des avant-gardes littéraires et intellectuelles

de la gauche en France, en Europe et très intensément aux États-Unis, –

le post-structuralisme et la psychanalyse en font partie. C’est ma

façon d’être une exilée à la recherche de l’impossible et de l’inconnu.

Le questionnement comme manière d'être. La mondialisation des idées

était en train de précéder la globalisation.

J’ai donc vraiment coupé les ponts avec la Bulgarie (c’était

facile, car il n’y avait ni téléphone, ni internet). Mais évidemment

pas avec mes parents (qui sont venus trois fois en France entre 1966 et

1989, grâce à l’intervention de Jacques Chaban-Delmas, contacté par ma

belle-famille bordelaise) et avec qui je communiquais par courrier.

C’est cette correspondance de 29 lettres qui a été interceptée et

divulguée, ce que je

trouve être la partie la plus sordide de cette

affaire. Je l'ai vécue comme un véritable viol. Au moment où le monde

entier s’émeut du fait que les données personnelles sont divulguées sur

les réseaux sociaux, mes lettres sont diffusées non seulement dans les

archives du KGB bulgare mais urbi et orbi sur la

terre entière et aucun journaliste ne s'en est ému. Pas plus que la

commission citée plus haut.

Il ne fallait surtout pas que je sois considérée comme

« ennemie du peuple » en Bulgarie car mes parents et ma sœur

y vivaient. J’essayais donc de garder des relations, en allant

périodiquement à l’ambassade pour obtenir éventuellement leurs visas.

J'y ai rencontré, fatalement, des apparatchiks, assis derrière des

bureaux, et dont je ne connaissais pas, ni ne me rappelle, tous les

noms. J'avais gardé quelques contacts avec la dissidence, je savais

qu’elle était de plus en plus en difficulté. Et je ne suis pas

retournée en Bulgarie pendant très longtemps.

J’y suis allée en 1983 avec

mon fils (né en 1975) pour qu’il rencontre mes parents. J’y suis

retournée en janvier 1989, avec François Mitterrand qui m’a intégrée

dans sa délégation, et nous avons rencontré des dissidents, comme le

futur président de la république Jeliu Jeliev ou mon amie Blaga

Dimitrova, future vice-présidente. Mon père est mort en septembre de la

même année, dans des circonstances bizarres, il paraît

qu'« ils » faisaient des expériences sur les vieillards, et

il fut incinéré contre sa volonté, les tombes étant réservées aux seuls

communistes, mais... si j'étais morte avant lui, de par ma notoriété,

ce privilège nous aurait été accordé ! J’ai eu l’impression qu’il

régnait une sorte de barbarie dans les rues, il y avait des queues

incroyables, la parole avait changé. En 25 ans, la langue était devenue

brutale, les gens s’insultaient.

Depuis la chute du Mur de Berlin, j’y suis allée de manière un peu

plus continue. En 2002, pour le décès de ma mère, et quand l’Université

de Sofia m’a donné le titre de docteur honoris causa. En

2014, l’Université a organisé un colloque autour de mon travail. J'ai

rencontré une jeune génération de philosophes, sociologues et analystes

d'une pensée exigeante, à l'affût des débats éthiques et politiques en

Europe et aux États-Unis, anxieux et lucides face aux difficultés du

pays qui s'enferre dans des imbroglios politiciens. Beaucoup de voix

connues et inconnues se sont élevées pour dénoncer le climat délétère

déclenché par les atermoiements de ladite « Commission ». Ces réactions montrent que divers courants traversent l'opinion, sur fond de malaise

européen.

Certains reprennent le dogme communiste et se tournent vers la

Russie, rempart et frère aîné. D'autres continuent à compter sur l'aide

européenne, avec et malgré les dérives mafieuses. D'autres encore,

assez rares mais tenaces, espèrent quelques réformes démocratiques,

favorisées par l'U.E. Mais dans cette impasse économique et politique,

les spectres du totalitarisme ne restent pas dans les placards de la

police. Ils envahissent de ressentiment la place publique. Je

l'entends, au sens de Nietzsche, comme une incapacité à transformer les

blessures du passé et les frustrations du présent en action, pour se complaire dans l'hostilité de la réaction. Dénonciations,

aigreurs et vengeances souvent recouvertes du fameux « sentiment national »,

aussi idéaliste que revanchard, et qui condamne cette partie de

l'Europe à se figer en banlieue de l’histoire en souffrance. Comme ces

prétendues « purges du passé », qui valident les méthodes

staliniennes en les reprenant sans mettre en question les procédés

policiers, sans interviewer les personnes diffamées, de sorte que le

régime dogmatique du passé se trouve relayé par le régime du buzz et de la pensée-calcul. A-t-on

oublié les procès staliniens ?

Il n'y a pas d'autre sortie de cet état toxique que d'approfondir

la réévaluation du phénomène totalitaire. En sondant ses différentes

facettes, son histoire institutionnelle, sa mémoire culturelle. En

écrivant « Bulgarie, ma souffrance » (1994), j'ai essayé de

ne pas oublier les racines religieuses.

La foi orthodoxe a des moments magnifiques, notamment dans la

compréhension de la douleur et du deuil, ses rituels sont une fête

sensorielle. Mais elle ne propose pas une véritable réflexion sur

l’indépendance de la personne. Il lui manque l'éloge, par la Renaissance,

de la liberté et de ses risques. La Bulgarie a vécu une sorte de

Renaissance précoce au Xe siècle, où le christianisme est passé dans un

peuple qui avait très peu d'État et très peu de structures

identitaires, mais qui, en créant un alphabet, le cyrillique, a créé et

sauvegardé sa culture. Puissant antidépresseur qui soude une nation.

En revanche, comme dans d'autres pays, notamment à l'Est de

l'Europe, les idées des Lumières ont été imposées par les élites, elles

n'ont pas suffisamment imprégné les comportements sociaux, les

structures institutionnelles. La pensée-interrogation fleurit dans les

universités, elle est absente dans l'espace politique. Sur ce socle, le

communisme a greffé des idéaux, mais la dérive totalitaire, écrasant

les aspirations sociales et sociétales, a détourné les citoyens de la

citoyenneté. L'après-communisme est aujourd'hui tenté par un retour

vers la spiritualité, la foi religieuse réactionnelle ou communiste,

qui progressent en doublure du spectacle, de la com' et du marketing

hyperconnecté, sans les mettre en question. Plus drastiquement que dans

les autres pays européens, les démocraties post-totalitaires sont

confrontées à la difficulté de faire vivre cette culture qu'on appelle

humaniste et dont la refondation permanente nécessite d'interroger l'identité,

la nation, la foi et le besoin de croire lui-même.

L’Europe porte une lourde responsabilité dans cette fracture qui se

creuse de nouveau et met à mal son projet. Si l'accomplissement des

droits de l'homme réside bien dans le respect de la personne et de sa

créativité singulière, le flux des capitaux ne suffit pas pour les

garantir et les transmettre. Un effort d'éducation, de formation et de

culture s'impose à tous, de l'école à l'entreprise, pour favoriser l'émergence d'une réévaluation du passé, qui

permettra que le ressentiment réactif cède la place à un renouvellement

politique démocratique.

Seule la vigilance de tous les instants, pour mettre la personne au centre de la médiasphère dont nous sommes les acteurs consumés, peut

encore nous sauver, Bulgarie, ma souffrance...

Julia Kristeva

Propos recueillis par Anne Dastakian

Dernier ouvrage publié :

JE ME VOYAGE (Mémoires). Entretiens

avec Samuel Dock, Fayard, 2017

Julia Kristeva : Bulgaria,

Post-Totalitarian Europe, And Me

It’s been three months

since the publication, via Sofia, of the Bulgarian communist

I

am indignant that Le

Nouvel Observateur, the

French weekly, openly declared me a KGB agent, spreading this falsehood with

the impunity of those who think they are not accountable to anyone. Had the journalists taken the trouble to read

the dossier fabricated by the totalitarian police, they would have found clear

evidence that I was the one subjected to surveillance, not the other way

around. Several journalists in Bulgaria in fact did just this (1), declaring the dossier empty and fit only to be thrown in the

trash, along with the tendentious Commission as well. Indeed some sixteen agents were sent my way

in order to contact just one “spy. ” They came up with imaginary pretexts to

justify their trips to the West. My

husband, Philippe Sollers, who distrusted pro-Soviet regimes, set his foot down

against our receiving any Bulgarian visitors. He adamantly refused to see them. That we dined with this apparatchik

who claims he “recruited” me is totally implausible.

Revealingly,

there are no informant missions assigned to me in these Stalinist archives.

Whoever devised them merely attributed opinions to me expressed in the 3rd

person, for example on Aragon or on the “Prague Spring” as being “not in the

spirit of the Bulgarian Communist Party…” Because I made such a lousy “spy,” Sollers seemed to become their

primary target. He was of interest to

them because he spent time at the Chinese and Albanian embassies, and (the year

the “Sabina” dossier got underway), founded the Maoist publication, Le Mouvement de juin 1971 ; it lasted three months

and was Voltaire-like in spirit. One could hardly say it weighed heavily on

Sino-Soviet relations! But the secret agents must have thought I’d be useful in

getting to this “dangerous” leader.

Allow

me to highlight the three stages of this dark business : 1/ The Secret Services create

a dossier, filling it with bureaucratic reports to give it weight ; 2/ The

« Lustration » (purging) Commission, in charge of the secret police

archives, tosses these dossiers to the public without analysing them, without

warning those they’ve accused of being collaborators and

traitors; 3/ Certain left-leaning publications in the West relate all this

without undertaking any real investigation, either because of a feeling of

guilt or because of an incapacity to analyse history.

It

is important to situate and analyse the ordeal that was inflicted upon me in

the larger, current context of post-totalitarian Europe where nostalgia for

communism gets entangled with nationalist demands

and threatens the viability of the European Union. I’m inclined to continue this reflection

elsewhere, limiting myself today to the symptomatic convergence between, on the

one hand, totalitarian systems that curtail the rights of men and women, and,

on the other hand, the media fever for grabbing scoops and spinning made-up news

that destroys reputations and infringes on people’s private lives with total

impunity. I do not rule out my going to court to bring this convergence to the

fore. But it is important

right now to reflect on this symptom’s components: when the debris of communism

is kindling nationalist movements in Eastern Europe and elsewhere, while the

press, the so-called “fourth power,” is losing its independence due to the

pitfalls of hyperconnected democracy.

I

experienced my departure from Bulgaria in 1965, with a scholarship from the

French government, as an exile. It was

the era of the thaw. Communist

education, beyond its “lying ideology” which Soljenitsyne decried as more

pernicious than restrictions on freedom, did nevertheless convey the

universalism of the Enlightenment. At

university we discussed Hegel’s dialectic, the critique it produced of

Marxism, Georg Luckas and his

disciples. The French Communist Party

was, for me, Aragon with his La Semaine sainte and Les Lettres françaises, and also the review, La Nouvelle Critique which opened up the

way to Tel Quel and structuralism.

The Parisian university and literary milieu welcomed and took me in right away;

it was interested in structuralism as it developed from Russian formalism, and

in a Marxism that could be interpreted. I saw a France that

was emerging from the Algerian war, trapped and guilt-ridden, but more French

than ever as it recovered its corrosive memory in the most audacious mouvements

of European thought.

I

enrolled at the École des Hautes Études and took Lucien Goldmann’s seminar. He was reinventing

Marx with Pascal, Hegel and structuralism, but also I studied with Roland

Barthes who was examining literature through the “nouveau roman” and

semiology. I was happy to belong to this

nomadic world of students from Germany, Italy, England, Latin America, and even

Eastern Europe (to a lesser degree) who, in the era preceding 1968, formed an

international community of researchers. I saw good fortune in my foreignness, even if I knew straight away that

I would never really be really French among the

French. I had a feeling of

weightlessness; it was painful but the experience left me open to questioning and

innovation. My political concerns, my

contacts with Eastern European dissidents tended to make me critical of

militants. My “political

dissidence », my « commitment »

was to seize the intellectual freedom on hand to develop and pursue

critical thought, a process begun in Bulgaria as a student. Through my contact

with avant-garde intellectuals and writers from the left in France, but also in

larger Europe, and very intensely in the United States, I further elaborated my

research in the fields of poststructuralism and psychoanalysis. My experience of exile can be summed up as

seeking the impossible and the unknown— questioning as a way of being in the

world. The globalisation of ideas was

preceding the globalisation of markets.

I

therefore cut ties with Bulgaria (this was easy in an era without the Internet

or phones) but obviously not with my family—who came to France three times

between 1966 and 1989 thanks to the intervention of Jacques Chaban-Delmas

(contacted by my in-laws in Bordeaux)—and with whom I corresponded by

mail. It was this correspondence of 29

letters that was intercepted and divulged in the Bulgarian dossier. This is

what I find to be the most sordid part of this whole affair—a total violation

of my privacy. At the very moment when the world is troubled by the fact that

personal information is being exposed without permission via social media, my

letters have been diffused, not only in the Bulgarian KGB archives, but

throughout the entire world and not a single journalist was troubled by that.

The Commission in Sofia wasn’t troubled either.

It

was imperative not to be considered an “enemy of the people” in Bulgaria

because my parents and my sister lived there. I tried to keep up good relations by going periodically to the embassy,

eventually to get their visas. I

inevitably had to deal with the

apparatchiks sitting behind desks, most of whose names I didn’t know, and can’t

remember. I had kept some contact with

the dissident movement and knew it had come upon hard times. I didn’t return to Bulgaria for a very long

time.

I

finally did return in 1983 with my son (born 1975) so that he could meet my

parents. I went back again in January

1989 with François Mitterrand who invited me to join his delegation; we met

with dissidents such as the future president of the Republic of Bulgaria, Jeliu

Jeliev, and my friend Blaga Dimitrova, future vice-president. My father passed

away in September of the same year, in strange circumstances: it seemed “they”

were doing experiments on the elderly and he was cremated against his

will. Graves, you see, were reserved for

communists only, but if I could just die before him, my notoriety would

guarantee us this privilege (of being together in the same grave)! I had the impression a kind of street gang

logic ruled the country; the lines were incredibly long everywhere, people

spoke differently. In the twenty-five

years I had been away, my mother tongue had become brutal, people spoke in a

volley of insults.

With

the fall of the Berlin Wall, I started going there more regularly. I returned in 2002 when my mother died and

when the University of Sophia granted me the title of Docteur Honoris

Causa. In 2014, the University of Sofia

organised a colloquium on my work. There

I met with a young generation of philosophers, sociologists and analysts

intellectually engaged in a demanding, thoughtful way by the political and

ethical debates in Europe and the United States. They were both anxious and

lucid about the challenges facing Bulgaria with its political imbroglios. Numerous voices, both known and unknown,

spoke out to denounce the deleterious climate created by the procrastinations

of the so-called “Commission ». With a troubled Europe as backdrop, these reactions show that diverse

currents still run through opinion in

the public sphere there.

Some

reclaim communist dogma and turn towards Russia—bulwark and Big Brother. Others continue to count on European aid,

with and despite of how funds inevitably drift toward the Mafia. Still others, rare but tenacious, are hoping

for the democratic reforms favored by the European Union. But during this economic and political

stalemate, the ghosts of totalitarianism do not stay hidden away in the police

filing cabinets. Those ghosts are

invading and filling the public square with resentment. My take on this is Nietzschean : I see

it as an incapacity to transform past wounds and current frustrations into

actions. Instead, we see a collective

wallowing in reactionary hostility. People cloak their bitterness, vengeance, and denunciations in that

notorious “national sentiment,” which is both idealistic and

spiteful—condemning this part of Europe to freeze in the suburbs of history,

suffering. Just as with these so-called

“purges of the past », validating Stalinist methods by taking them up again

and failing to question police proceedings—and without interviewing those who

are being slandered. And all of this happens in such a way that the dogmatic

regime of the past is relayed forward to the present by the new regime of the

« buzz » and a form of thinking based only in calculus. Have we

really forgotten the Stalin Show Trials?

The

only way out of this toxic state is to deepen our understanding of

totalitarianism by probing its different facets, its institutional history, and

its cultural memory. In writing Bulgaria, My Suffering (1994), I tried not

to forget to emphasize religious roots as well.

The

Orthodox faith has magnificent moments, notably its understanding of pain and

grief, with rituals that offer a sensorial celebration. But it does not allow for any real reflection

on personal freedom. It lacks the

Renaissance’s hymn to liberty and its risks. Bulgaria went through a kind of precocious Renaissance in the tenth

century when Christianity spread among a people without a firmly implanted

national identity; yet by devising the Cyrillic alphabet, this people created

and safeguarded its culture. Cyrillic

worked like a powerful anti-depressant, capable of welding together a nation.

On

the other hand, in Bulgaria, as in other countries, especially in Eastern

Europe, Enlightenment ideals were imposed by an elite and did not sufficiently

integrate themselves into social behaviour and institutions. Though humanist thinking and questioning

flourished in universities, it was absent in the political sphere. Upon this bedrock, communism grafted its

ideals, but wayward totalitarianism trampled social and societal aspirations,

turning citizens away from their citizenship. Post-communism is today tempted by a return to spirituality, whether

reactionary or communist religious faith—one which moves alongside our

spectacle-oriented, hyperconnected, marketing-driven society without

questionning it. More drastically than in other European countries,

post-totalitarian democracies are confronted with the difficulty of bringing to

life a humanist culture whose refoundation, ever in progress, requires the

continual questionning of identity, nation, faith, and the need to believe itself.

Europe

carries a heavy responsibility within this deepening fracture that is crippling

its overarching project. If the

accomplishment of human rights for all means guaranteeing respect for the

person and his or her creative singularity, the movement of capital is not a

sufficient guarantee these rights will be upheld. Education, professional

training, and culture must be our focus, in our schools and in our

businesses. Only in this way can we

foster the much needed re-evaluation of the past so that reactive resentments

can give way to political and democratic renewal.

The

only way we can save ourselves is by exercising constant

vigilance that it is the human being who

is at the center of the media-sphere where we are all such consumed actors.

Bulgaria, my suffering…

JULIA KRISTEVA