|

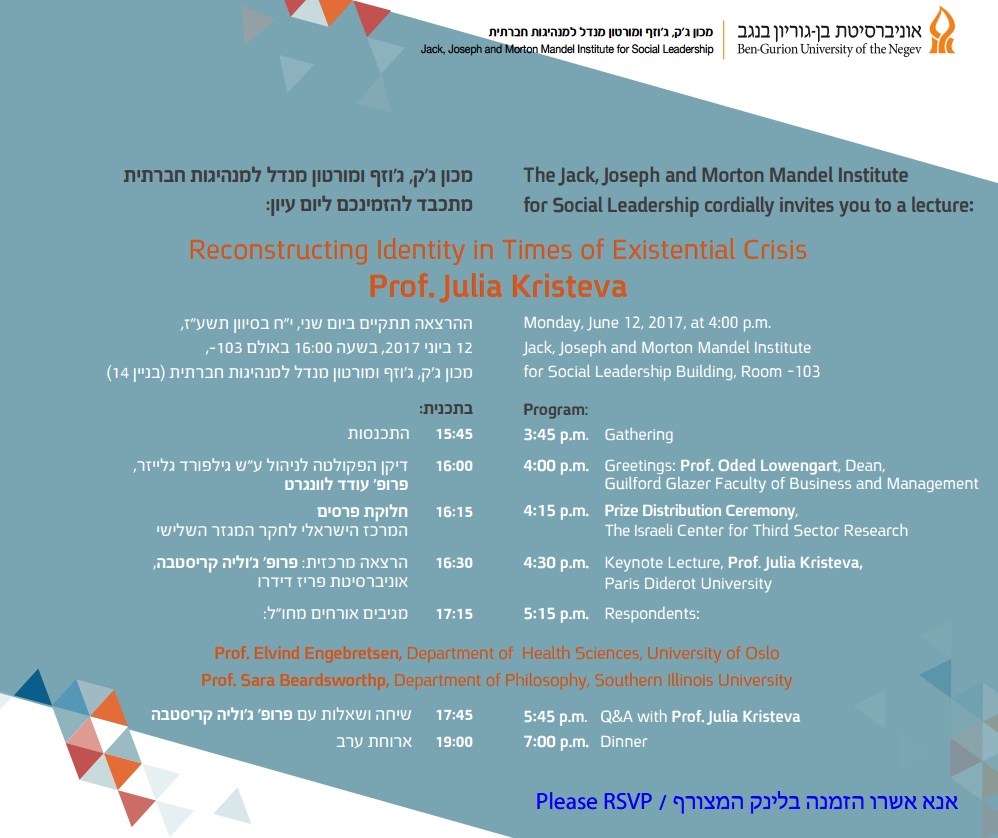

Reconstructing Identity in Times of Existential Crisis

Nous le savons

tous : sous le couverts des crises – tremblement à la présidence des

Etats-Unis d’Amérique, recomposition politique en France, montée nationaliste

en Europe, Daesh combattu mais pas vaincu, incapacités des démocraties à faire

face à l’islam radical, etc. – je ne saurais les énumérer toutes, une mutation

anthropologique est en cours. Certains s’en réjouissent, d’autres craignent une

nouvelle apocalypse. A l’heure où nous parlons, rien n’est joué, tout peut

basculer.

Je me définis comme

une pessimiste énergique. Et je prétends qu’il nous faut continuer

inlassablement la refondation de l’humanisme, celui qui s’est affirmé au siècle

des Lumières, en « coupant le fil avec la tradition religieuse »

(selon Alexis de Tocqueville et Hannah Arendt). Une refondation complexe,

difficile et de longue haleine.

Pendant la récente

campagne présidentelle française, en reprenant l'anaphore répétée du candidat

Hollande : « Moi Président » pour décliner son programme, une

radio a proposé à diverses personnalités de la reprendre pour proposer

« leur » programme. « Moi Présidente », j’ai dit que je

mettrai au centre du pacte politique LA PERSONNE.

Je vous remercie de

me donner l’occasion de développer cette vision, devant les collègues,

chercheurs et étudiants de votre prestigieuse Université Ben Gurion, à

l’initiative de la Fondation Mandel et tout particulièrement du Prof. Pierre

Kletz.

Les innovations

scientifiques, les promesses du trans-humanisme, et dès maintenant les

modifications de nos comportements qu’induisent les nouvelles technologies et

l’hyperconnexion, transforment cette construction psycho-sexuelle qu’on appelle

une personne. Pour le meilleur et

pour le pire. Notre monde globalisé favorise, comme jamais dans l’histoire

humaine, les rencontres mais aussi les confrontations entre les individus, les

nations, les cultures. Certains réagissent en essayant de ressouder, voire de

barricader les identités : nationalismes, souverainismes, populismes se

radicalisent. D’autres rêvent d’une humanité golablisée heureuse, diversifiée

et fraternelle.

Je ne pense pas que

l’identité soit un archaïsme. L’identité est un anti-dépresseur qu’il convient

d’utiliser avec précaution et d'accompagner de soins délicats.

J'aborderai trois

thèmes sur l'identité :

- L’identité des

adolescents radicalsés, suivie à la Maison des adolescents (Hôpital Cochin,

Paris) où se poursuit mon séminaire de l’Université Paris-VII, sur le besoin de croire : j’insisterai sur

la place des idéaux dans la construction de l’identité .

- L’accompagnement

des personnes défavorisées, en situation

de précarité ou de handicap : j’insisterai sur la nécessité de sortir

du paradigme du « manque » et de la « pauvreté » pour

centrer l’accompagnement sur le respect de la singularité.

- Je finirai, dans

cette approche de l’identité, sur la conception de la liberté, appréhendée non comme une transgression, mais comme une

créativité.

1. Comment peut-on être djihadiste ?

Rien qu'en France,

les attentats djihadistes de Charlie Hebdo, Hyper Casher, Bataclan, Nice

et j’en passe, ont fait 234 morts, 785 blessés... Le« mal radical »désigne, pour Kant, le désastre de

certains humains qui considèrent d’autres humains superflus, et les exterminent froidement. Hannah Arendt avait

dénoncé ce mal absolu dans la Shoah.

Aujourd’hui, les

adolescents de nos quartiers pauvres, issus de familles croyantes ou non,

s’avèrent être le maillon faible où se délite, en abîme du pacte social, le

lien hominien lui-même (le conatus de

Hobbes et de Spinoza). Et la reliance entre les vivants parlants explose dans

un monstrueux déchaînement de la pulsion de mort.

Comment et

pourquoi ?

Je ne saurais développer

les causes géopolitiques et théologiques de ce phénomène : la

responsabilité du post-colonialisme, les failles de l’intégration et de la

scolarisation, la faiblesse de « nos valeurs » qui gèrent la

globalisation à coups de pétrodollars appuyés sur des frappes chirurgicales, le

rétrécissement du politique en serviteur de l’économie par une juridiction plus

ou moins soft ou hard…

Des chercheurs ont

le courage d’interroger l’Islam dans son rôle de législateur absolu, une

« orthodoxie normative » (selon Abdennour Bidar) qui n’étudie pas le

canon religieux, mais le réduit au « comment s’organiser entre nous » pour l'appliquer et invitent leurs

coreligionnaires à questionner leur rituel contraignant, à l’historiciser, à le

contextualiser : pourquoi ?

quand ? avec qui ? A l’Absolu coranique, où Allah est perçu comme

un « moteur immobile » quasi aristotélicien – il manquerait, dit-on,

un approfondissement du « meurtre du père », qui a transformé, dans

l’histoire de l’humanité, la « horde primitive » en « pacte

social ». Cette élucidation du parricide originaire en doublure de la Loi,

qui s’est produite dans le judaïsme et le christianisme, a ouvert la voie à

l’infini questionnement rétrospectif sur l’hainamoration (Lacan)

constitutive du lien anthropologique.

La globalisation et

ses crises endémiques, et l’impuissance de l’Europe en elle, ne facilitent pas

ce processus de réévaluation des valeurs. Mais elles rendent nécessaire une

refondation totale, à réinventer, sans suivre aucun modèle préalable, fût-il celui

des Lumières. D’autant que la pensée procédurale de la modernité

entrepreneuriale, le comment à la

place du pourquoi, l’assujettissement

au calcul technique, le retrait des individus interconnectés, avec mort à soi et exaltation virtuelle, ne sont pas en

contradiction avec des comportements rituels d’un autre âge : nos

barbaries modernes se reconnaissent dans les anciennes et vice versa, leurs

logiques sont compatibles.

En amont des

mesures punitives, sécuritaires ou militaires, il ne suffit pas de repérer

comment se recrutent les djihadistes sur Internet ou dans les prisons, il

importe d’accompagner les jeunes en voie de radicalisation, avant qu’ils ne

rejoignent les camps de Daesh, pour revenir en kamikazes ou, éventuellement, en

repentis plus ou moins sincères et réinsérés.

L’écoute

psychanalytique est partie prenante de cet accompagnement. Pourquoi « la

pulsion de mort » remplace-t-elle – au travers de l’adhésion à un corpus

religieux – le besoin pré-religieux, anthropologique, de croire chez les adolescents

qu’on dit « fragiles » ?

Le besoin de croire

Deux expériences

psychiques confrontent le clinicien à cette composante anthropologique

universelle que j’appelle le besoin de

croire pré-religieux.

La première renvoie

à ce que Freud, répondant à la sollicitation de Romain Rolland, décrit non sans

réticences, comme le « sentiment océanique » avec le contenant

maternel (Malaise dans la civilisation, 1929).

La seconde concerne

l’« investissement » : Besetzung (allemand), cathexis (anglais) -

°kred en sanscrit, °amuna en hébreu, °credo en latin – et/ou l’« identification primaire » avec

le « père de la préhistoire individuelle » : amorce de l’Idéal

du moi, ce « père aimant », antérieur au père œdipien qui sépare et

qui juge, aurait les « qualités des deux parents » (Le Moi et le Ça, 1923).

La croyance dont il

s’agit ici est une certitude inébranlable : plénitude sensorielle et

vérité ultime que le sujet éprouve comme une sur-vie exorbitante,

indistinctement sensorielle et mentale, à proprement parler ek-statique (dans

le « sentiment océanique ») et dépassement de soi dans la

« transcendance » de ce premier tiers qu’est le père

(l’« unification » avec la paternité aimante).

Ce besoin de croire satisfait, et offrant

les conditions optimales pour le développement du langage, apparaît comme le

fondement sur lequel pourra se développer une autre capacité, corrosive et

libératrice : le désir de

savoir.

L'adolescent est un

croyant

La curiosité

insatiable de l'enfant-roi fait de lui un « chercheur en

laboratoire » nous dit Freud dansTrois

Essais sur la théorie de la sexualité (1905), qui veut découvrir

« d’où viennent les enfants ». L’éveil de la puberté implique chez

l'adolescent une réorganisation psychique sous-tendue par la quête d’un idéal,

d'un dépassement de soi et du monde : l'adolescent désire s’unir à une

altérité idéale, ouvrir le temps dans l’instant, l’éternité maintenant. C'est

un « croyant » : il croit dur comme fer que le paradis existe,

que la satisfaction absolue des désirs existe, que l’objet d’amour idéal est à

sa portée, car il est résorbé dans l’investissement, confondu avec le

besoin de croire. Croire, au sens de la foi, implique une passion assimilatrice

pour la relation d'objet : la foi veut tout, elle est potentiellement

intégriste, comme l'est l'adolescent.

Cependant, nos

pulsions et désirs étant ambivalents, sado-masochiques, la réalité impose

frustrations et contraintes, et l’adolescent, soufflé par son pseudo-objet

idéal, éprouve cruellement l'impossibilité de sa croyance. Dès lors, cette

passion s'inverse en punition et autopunition : la déception-dépression-suicide

; la poussée destructrice de soi-avec-1'autre : le vandalisme de la petite

délinquance ; la toxicomanie qui abolit la conscience, mais réalise la croyance

en l'absolu de la régression orgasmique dans une jouissance

hallucinatoire ; l'anorexie qui attaque la lignée maternelle et

révèle le combat de la jeune fille contre la féminité, dans le fantasme d'une

spiritualité, elle aussi absolue, où le corps tout entier disparaît dans un

au-delà à forte connotation paternelle.

Croyance et

nihilisme : les maladies de l'âme

Structurée par

l'idéalisation, l'adolescence est une maladie

de l'idéalité (Jeannine Chasseguet-Smirgel) : soit l'idéalité lui

manque ; soit celle dont elle dispose ne s'adapte pas à la pulsion

pubertaire et à son besoin de partage avec un objet absolument comblant, sans

manque. Nécessairement exigeante et hantée par l’impossible, la croyance

adolescente se déroute dans la perversion,

elle côtoie ainsi et inexorablement le nihilisme

adolescent : Dostoïevski fut le premier à sonder ces nihilistes

possédés. Puisque le paradis existe (pour l'inconscient), mais « il »

ou « elle » me déçoit (dans la réalité), je ne peux que

« leur » en vouloir et me venger ; la délinquance s'ensuit. Ou

bien : puisque ça existe (dans l'inconscient), mais « il » ou

« elle » me déçoit ou me manque, je ne peux que m'en vouloir et me

venger sur moi-même contre eux : les mutilations et les attitudes

autodestructrices s'ensuivent.

La déliaison

Endémique et

sous-jacente à toute adolescence, la maladie

d’idéalité risque d’aboutir à une désorganisation psychique profonde, si le

contexte traumatique, personnel ou socio-historique s’y prête. L’avidité de

satisfaction absolue se résout en destruction de tout ce qui n’est pas cette

satisfaction, abolissant la frontière entre moi et l’autre, le dedans et le

dehors, entre le bien et le mal. Aucun

lien à aucun « objet » ne subsiste pour ces « sujets »

qui n’en sont pas, en proie à ce qu’André Green appelle la déliaison (Cf. André Green,

La Déliaison, 1971-1992) avec ses deux versants : la

désubjectivation et la désobjectalisation. Où seule triomphe la pulsion de

mort, la malignité du mal.

Déni ou ignorance,

notre civilisation sécularisée n’a plus de rites d’initiation pour les

adolescents. Les pratiques culturelles et cultuelles, connues depuis la

préhistoire et pérennisées dans les religions constituées, authentifiaient le

syndrome d’idéalité des adolescents et aménageaient des passerelles avec la

réalité communautaire. La littérature, en particulier le roman dès qu’il

apparaît à la Renaissance, savait narrer les aventures initiatiques de héros

adolescents : le roman européen est un roman adolescent. L’absence de ces

rites laisse un vide symbolique, et la littérature-marchandise ou spectacle est

loin de panser les angoisses de ce croyant nihiliste qu’est l’adolescent

internaute qui préfère les jeux vidéo aux livres.

Aux XIXe et Xxe siècles,

l’enthousiasme idéologique révolutionnaire, qui « du passé faisait table

rase », avait pris le relais de la foi : la « Révolution »

a résorbé le besoin de se transcender, et l’espoir que l’« homme

nouveau », femme comprise, saurait jouir enfin d’une satisfaction totale

s'est effondré, quand le totalitarisme a mis fin à ce messianisme laïc, qui

avait expulsé la pulsion de mort dans l’« ennemi de classe », et

réprimé la liberté de tous de croire et de savoir.

En dessous du heurt

des religions

Prise au dépourvu

par le malaise des adolescents, la morale laïque semble incapable de satisfaire

leur maladie d’idéalité. Le traitement religieux de la révolte par les

quiétistes n'y parvient pas non plus. L'aspiration paradisiaque est

instrumentalisée par les intégristes qui le pousse au combat armé ce croyant paradoxal,

forcément nihiliste, parce que pathétiquement idéaliste, qu'est l'adolescent

désintégré, désocialisé dans l'impitoyable migration mondialisée imposée par

l’ultralibéralisme.

Il existe également

des « fausses » personnalités, « clivées », « comme

si » : chez ces adolescents (ou jeunes adultes) en apparence bien

socialisés, et dotés de performances techniques plus ou moins appréciables

(conformité au « comment »), les crises affectives

inabordables (soustraites au « pourquoi » du langage et de la pensée,

et en ce sens « muettes ») se manifestent brusquement dans des

conduites destructrices, au grand étonnement des proches qui ne se doutaient de

rien... En dessous du « heurt

de religions », la déliaison nihiliste

est plus grave que les conflits interreligieux, parce qu'elle saisit plus en

profondeur les ressorts de la civilisation, mettant en évidence la destruction

du besoin de croire pré-religieux, constitutif de la vie psychique avec et pour

autrui.

Ces états-limites

déferlent dans des catastrophes sociopolitiques, telle l’abjection de

l’extermination que fut la Shoah, une horreur qui défie la raison. Ils prennent

de nouvelles formes dans le monde globalisé, dans la foulée des maladies

d’idéalité.

L’expérience

psychanalytique ne se contente pas d’être un « moralisme

compréhensif » (contre lequel Lacan mettait en garde les psychanalystes).

Dans l’intimité du transfert-contretransfert, elle cherche à affiner

l’interprétation de cette malignité potentielle de l’appareil psychique qui se

révèle dans les maladies d’idéalité. Que par ailleurs, ni la mystique ni la

littérature n'ont ignorées.

La psychanalyse se

réinvente

Souad est une jeune

fille de 14 ans, de famille musulmane. Elle avait été suivie pour

anorexie : lente mise à mort du corps, tuer la femme et la mère en soi,

abandonnées et incomprises. Deux ans plus tard, l’état de guerre de Souad a

changé. Burqa, silence, et Internet où, avec des complices inconnus, elle taxe

sa famille d’« apostats, pires que les mécréants », et prépare son

voyage « là-bas », pour se faire épouse occasionnelle de combattants

polygames, mère prolifique de martyrs ou kamikaze elle-même.

Souad a commencé

les entretiens avec l'équipe mutilculturelle et mixte de psychothérapie

analytique par une provocation, en disant qu’elle était un « esprit

scientifique », forte en maths et physique-chimie, et que « seul

Allah disait vrai et pouvait la comprendre ». La littérature « ne lui

disait rien » et elle « détestait les cours de français et de

philo » qu’elle « séchait au possible ».Mais Souad a trouvé du

plaisir à se raconter, à jouer avec l’équipe ; des transferts éclatés et

ténus se profilant, comme avec une nouvelle famille recomposée, elle a pu rire

avec les autres et d’elle-même. Et renouer avec le français ; apprivoiser

avec le langage ses pulsions destructrices et ses sensations en souffrance.

D’autres ados accompagnés par l’équipe fréquentaient des ateliers d’écriture et

de théâtre. Souad leur a emprunté un livre de poèmes arabes traduits en

français. Elle sèche moins les cours de français. Et elle a remis son jean.

Roland Barthes

écrivait que si vous retrouvez la signification dans la plénitude d’une langue,

« le vide divin ne peut plus menacer ». Le trop-plein du divin

totalitaire non plus. Souad n’en est pas encore là. Ce sera long. Elle aurait

récemment investi unethérapeute,

avec laquelle elle est en train d’élaborer la reliance maternelle. Mais combien de jeunes n’auront pas sa chance

de rencontrer une écoute analytique ? Et de renouer avec une identité en

mouvement ?

2.

Privation vs

possession : « avoir » ou « être »

·

Depuis Aristote (la Physique), qui caractérisait les

aptitudes humaines à partir de la catégorie du défaut, la stérésis, en passant par l’Evangile selon

Matthieu (25: 35 sq), qui la traduit par la notion de

« pauvreté » (« Car j’ai eu faim, et vous m’avez donné à

manger ; j’ai eu soif […] ; j’étais un étranger […] ; nu […] ;malade […] ;en

prison […]. Chaque fois que vous l’avez fait à l’un des moindres de mes frères,

vous me l’avez fait à moi. »), en passant par les Ordres caritatifs et

jusqu’au regard sécularisé sur la précarité et le handicap, une même tonalité

perdure. Entendons : certaines personnes sont « en défaut »,

diversement pauvres, « stériles »... ; il ne nous reste qu’à

partager leur impuissance dans notre passion, et sur cette com-passion avec le « manque à être/avoir »,

de fonder le « bien vivre ». Telle est l’éthique de l’humanisme

chrétien, qui se prolonge plus ou moins sournoisement.

Comprenez-moi

bien : il ne s’agit pas d’ignorer le pathologique et encore moins de

l’abolir – l’inévitable de la norme nous l’interdit – mais bien de le

compléter.

Tel quel, il risque

d’enfermer le sujet handicapé dans une position d’« objet de

soin(s) », de « pris en charge », au mieux par la

« tendresse », souvent en négligeant et les connaissances

scientifiques qui parviennent à identifier et à traiter les symptômes

spécifiques, et les capacités créatrices qui existent, y compris chez les plus

souffrants.

Je soutiens, au

contraire, contre le paradigme de l’« avoir » (et/ou de « ne pas

avoir ») et de la stéresis, le

paradigme de la singularité de l’être.

La singularité comprend jusqu’au déficit lui-même, en tant que révélateur de la

finitude et des frontières du vivant, mais ne l’enferme pas : il n’est pas

une privation, une défaillance ni un péché. La contingence du singulier est positive, en elle « être » et

« étant » se conjoignent. La contingence du singulier

« handicapé » me révèle ma propre singularité de

« possédant » dit « valide », que je n’exalte ni ne nie,

mais que j’apprivoise pour de bon à partir de la singularité du

« manquant ». C’est la mortalité en marche qui me touche en lui, j’en

suis, elle me tombe dessus, je l’accompagne, je l’aime telle qu’elle est. Par

mon amour pour l’autre singulier, je le porte à son développement spécifique,

singulier, – et au mien, également spécifique et singulier.

L’ex-chanoine

Diderot avait repris quant à lui, d’une autre façon, qui est celle de

l’humanisme moderne, cette « singularité positive », quand il avait

entrepris de transformer – pour la première fois au monde – la personne handicapée en sujet politique. Les handicapés ont tous

les droits, « naissent libres et égaux en droits », laisse-t-il

entendre en substance dans sa Lettre sur

les aveugles à l’usage de ceux qui voient (1749). Et les Déclarations des droits de l’homme prendront

beaucoup de temps pour mettre en pratique ce principe qui transforme, en

positivité efficiente, la finitude en acte dans la personne handicapée. Le

droit à la « compensation personnalisée » de la loi française de 2005

en est un aboutissement.

Pourtant, afin

d’accomplir cette ambition de l’humanisme moderne, il nous faudrait réinventer

ce corpus mysticum que Kant évoque à

la fin de la Critique de la raison pure (1781),

afin que la singularité de la personne avec handicap puisse transformer les normes elles-mêmes en concept dynamique,

évolutif : réinventer l’amour comme union avec la singularité du tout

autre.

En d’autres

termes : à la solidarité intégratrice avec les défaillants, il importe de

substituer l’amour des singuliers. Quel amour ? L’amour en tant que désir

et volonté pour que le singulier puisse élucider, faire reconnaître et

développer en la partageant sa propre singularité. Bien plus qu’une solidarité,

encore balbutiante, seul cet amour-là peut conduire la singularité positive (et

non pas « manquante ») dans une société, qui est fondée sur la norme

sans laquelle, je l’ai dit, il n’y a pas de lien, mais peut aussi faire évoluer

les normes.

En ouvrant la question

de l’amour, « transfert continûment élucidé » dans l’accompagnement

de la personne handicapée, c’est à la formation

des personnels intervenants que je pense, vous l’avez compris, et à la

place de la psychanalyse dans ce domaine complexe et polémique. Nous y

reviendrons sans doute dans le débat.

Permettez-moi de

conclure – sur un ton plus personnel – en rappelant le rôle maternel dans cette

épreuve. Tout soignant, toute soignante, développe en soi la bisexualité

psychique : féminin et masculin, reliance maternelle et cadrage paternel,

empathie et distance, affects et lois.

3.

Quelle

liberté ?

Pour finir, quelle liberté dans ce contexte ?

La liberté n’est pas une notion

psychanalytique. Freud n’emploie que rarement le terme de « poussée

libertaire » (Freitheitsdrang) :

ambivalente, à la fois révolte contre l’injustice et source de progrès, mais

aussi individualisme indompté hostile à la civilisation, la liberté est freinée

par le besoin de sécurité et, dès les débuts de l’hominisation, jugulée par la

conscience morale qui impose le renoncement aux pulsions. Certes, mais

l’expérience psychanalytique propose une autre version de la liberté, qui

s’appuie sur la possibilité du transfert-contretransfert d’optimaliser la vie psychique, pour établir de

nouveaux liens et développer des créativités (car telle fut l’éthique qui

préside aux fondations de la psychanalyse, bien que la formulation en revienne

à Winnicott). Cette vision de la liberté comme optimalisation de la vie

psychique s’inscrit dans un courant

philosophique, lui aussi d’inspiration kantienne, selon lequel la liberté n’est pas une révolte-négation des interdits de la poussée hormonale, électrique ou

libidinale ; la liberté est une initiative, un recommencement de soi

dans le temps : Selbstanfanf (Kant), Self-beginning. Mais, tandis que certains tendent à réduire cette liberté-initiative dans la liberté d’entreprendre, dans

les procédures de l’adaptation à la

production-reproduction-communication-marketing, d’autres, au contraire,

privilégient, dans l’initiative, la

découverte de la liberté-révélation par

et dans la rencontre avec l’autre.

La liberté n'est

pas un choix (« et si c’était mon choix de porter la burqa, d’aller

rejoindre Daesh? »), c'est une construction-dépassement

de soi avec et vers l’altérité de l’autre. Tandis que la vieille Europe

s’essouffle en mesures impuissantes, et que, de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique,

dominent le schéma binaire gagnant/perdant et la politique spectacle,

l’engagement pour la vie psychique s’annonce indispensable, ardu et de longue

haleine ;je le répète.

Et je m’adresse aux

étudiants dans cette salle, qui se consacrent à l’accompagnement des personnes,

ou bien à ceux qui, quelle que soit leur profession, auront le souci du lien

social-politique-éthique. Il n’y a pas d’autre voie pour affronter les

surprises de la mutation anthropologique en cours. Il nous revient, il VOUS

revient, d'approfondir et de disséminer cette liberté vitale que nous cherchons

à faire advenir au plus intime de ceux qui nous font confiance, et même chez

ceux qui répandent le « mal radical ». Et pour cela, il nous/vous

faut solliciter des complicités, disséminer notre/votre pratique, et sans

relâche approfondir et innover notre/votre recherche.

JULIA KRISTEVA

12 juin 2017, à l'Université de Ben Gourion

|

|

|

Reconstructing Identity in Times of Existential Crisis

We all know that

under the guise of crises—presidential turbulence in the United States of

America, political recomposition in France, the rise of

nationalism in Europe, Daesh (ISIS) fought but not defeated, the incapacity of

democracies to successfully face down radical Islam, etc.—I cannot enumerate

them all, but suffice it to say that an anthropological transformation is

underway. Some rejoice, others fear a new apocalypse. Now, as we speak, nothing

can be taken for granted, anything could topple.

I define myself as an

energetic pessimist. And I say that we must tirelessly continue the rebuilding

of humanism, that Enlightenment philosophy, by "cutting ties to religious

tradition" (according to Alexis de Tocqueville and Hannah Arendt). And it

will be a complex, difficult, and long-term rebuilding.

During the previous

French presidential campaign, one radio station asked various personalities to

propose “their own” program: “What would you do if you were president?” I said

that “if I were president,” I would put the INDIVIDUAL at the center of the

political pact.

Thank you for giving

me the opportunity to expand on this vision here in the presence of the

colleagues, researchers, and students of your prestigious Ben Gurion

University, at the initiative of the Mandel Foundation and especially Prof.

Pierre Kletz.

Scientific innovations,

the promises of transhumanism, and now the changes in our behavior that new

technologies and hyperconnectivity bring about,

transform the psychosexual construction that is called a person. For better and for worse. Our globalized world promotes, as

never before in human history, encounters but also confrontations between

individuals, nations, and cultures. Some react by trying to strengthen and even

secure identities; nationalisms, sovereignties and populisms are becoming

radicalized. Others dream of a happy, globalized, diversified, and fraternal

humanity.

I do not think identity is archaic. Identity is an

anti-depressant that should be used with caution and accompanied by delicate

care.

I will address three

themes on identity:

- The identity of

radicalized teens, who are being cared for at the Maison des Adolescents

(Cochin Hospital, Paris), where my University Paris-VII seminar on the need to believe takes place; here, I

will insist on the role of ideals in

the construction of identity.

- Caring for the disadvantaged, the disabled, and those in

precarious situations; here, I will insist on the need to give up the

paradigm of "lack" and "deficiency" to focus our attention on

respecting singularity.

- Finally, in this

approach to identity, I will finish on the concept of freedom, seen not as a transgression, but as something creative.

1. How Can One Be a Jihadist?

In France alone, the

Jihadist attacks on Charlie Hebdo,

Hyper Casher, the Bataclan, Nice, and so on, left 234 dead, 785 injured, and

more. We are facing what Kant called "radical evil", designating

by this word the disaster of certain humans who consider other humans superfluous, and exterminate them

coldly.

Today, the

adolescents in our poorest neighborhoods, whether from religious or

non-believing families, are the weakest link, where the hominian bond itself (the conatus of Hobbes

and Spinoza) crumbles into the abyss of the social pact. And the connection

between the speaking living explodes in a monstrous outburst of the death drive.

How and why?

I cannot speak to the

geopolitical and theological causes of this phenomenon; the responsibility of

post-colonialism, the flaws in integration and schooling, the weakness of

"our values", which manage globalization with petrodollars supported

by surgical strikes, the shrinking of politics into the servant of the economy

via a jurisdiction that is softer or harder.

Some researchers have

the courage to question Islam in its role of absolute legislator, a

"normative orthodoxy" (according to Abdennour Bidar) inviting us to historicize it. One might say

that the elucidation of the original parricide in the doubling of the Law,

which founded the social pact in the history of mankind, is lacking, and opened

the way to infinite retrospective questioning of the "hainamoration (Lacan) that constitutes the anthropological link.

Globalization and its

endemic crises, and the powerlessness of Europe in it, do not facilitate the

process of reevaluating modern ethical values. But they do make the total refounding of humanism necessary, so as to reinvent,

without following any previous model, even the values of the Enlightenment.

Particularly as the procedural thinking of entrepreneurial modernity, the how instead of the why, the dependence on technical calculation, the withdrawal of

interconnected individuals, with death of the self and virtual exaltation, do not contradict the rituals of

fundamentalist behaviors of another age. Our modern barbarities recognize

themselves in those of another age and vice versa; their logics are compatible.

Why, in those

adolescents we label "fragile", does the "death drive"

replace the pre-religious, anthropological need to believe through adherence to

a religious corpus? Repentent and headed for

radicalization, psychoanalysis can help them.

The need to believe

Two psychic

experiences confront the clinician with this universal anthropological

component which I call the pre-religious need

to believe.

The first refers to

what Freud described as the "oceanic feeling" with the maternal

container (Civilization and its

Discontents, 1929).

The second is called "cathexis"

in English, bezetsung in German, investissment in French, kred in Sanskrit, emuna in Hebrew, and credo in

Latin, and designates the "primary identification" with the

"father in the personal prehistory". This "loving father", prior

to the Oedipan father who separates and judges, has

the "qualities of both parents" (The

Ego and the Id, 1923) and gives rise to

the ideal ego and all ideals.

The belief in question here is not a

hypothesis; it is unshakeable certainty: sensory fullness and ultimate truth

that the subject experiences as an exorbitant "sur-vival",

indistinctly sensory and mental, something that is strictly speaking ek-static (in the "oceanic feeling"); and

transcendence of the self in the "transcendence" of this first third

party that is the father (the "unification" with loving fatherhood).

This need to believe satisfied, and offering

optimal conditions for the development of language, appears to be the

foundation on which can develop another ability, one that is corrosive and

liberating: the desire to know.

The teenager is a

believer

The insatiable

curiosity of the child-king makes him a "laboratory researcher",

Freud tells us in Three Essays on the

Theory of Sexuality (1905), and one who wants to find out "where

children come from". For adolescents, the awakening of puberty involves a

psychic reorganization underpinned by the pursuit of an ideal, the surpassing

of oneself and the world; teenagers want to join an ideal otherness, opening time in an instant, eternity now. They are

"believers": they firmly believe that paradise exists, that the

absolute satisfaction of desires exists, that the object of ideal love is

within their reach, for they are absorbed in cathexis, which they have conflated

with the need to believe. To believe, in the sense of faith, implies an

assimilative passion for the object relation: faith wants everything, and is

potentially fundamentalist, as is the adolescent.

However, as our impulses

and desires are ambivalent and sadomasochistic, reality imposes frustrations

and constraints, and the adolescent, blown by his ideal pseudo-object, cruelly

experiences the impossibility of his belief. From then on, this passion is

reversed in punishment and self-punishment—disillusion-depression-suicide; the

self-destructive urge of self-with-other—the vandalism of petty delinquency;

the drug addiction that abolishes consciousness but realizes belief in the

absolute of regression in a hallucinatory pleasure; the anorexia that attacks

the maternal line and reveals the girl's struggle against femininity in the

fantasy of a spirituality, itself also absolute, in which the whole body

disappears in a beyond with a strong paternal connotation.

Belief and nihilism:

diseases of the soul

Structured by

idealization, adolescence is a disease of

ideality: either ideality is lacking; or the ideals that adolescents possess

do not adapt themselves to the pubertal drive and its need for sharing with an

absolutely fulfilling object, without lack. Necessarily demanding and haunted

by the impossible, the adolescent belief directs itself toward eroticized destructiveness, and thus

inexorably rubs shoulders with teenage

nihilism; Dostoevsky was the first to fathom these possessed nihilists.

Since paradise exists (for the unconscious), but "he" or

"she" disappoints me (in reality), I can only be upset with

"them" and avenge myself; delinquency ensues. Or, since it exists (in

the unconscious), but "he" or "she" disappoints or is

missed by me, I can only blame myself and avenge myself against them; mutilation

and self-destructive attitudes follow.

The unbinding process

Endemic to and

underlying all adolescence, the disease

of ideality may lead to profound psychological disorganization if the

traumatic, personal, or socio-historical context lends itself to that. The

greed for absolute satisfaction is resolved in the destruction of all that is

not this satisfaction, abolishing the boundary between the self and the other,

within and without, good and evil. No

link to any "object" remains for those "subjects" who

are not yet independent, prey as they are to what psychoanalyst André Green

calls the unbinding process (Cf. André

Green, La Déliaison,

1971-1992) with its two sides, desubjectification and deobjectification. Where only the death drive

triumphs, aggravated by drug abuse, there lies the malignity of evil.

Whether through

denial or ignorance, our secularized civilization no longer has any initiation

rites for adolescents, which once helped them connect to the community reality,

and exposes them to the traumatic symbolic void. Even literature no longer suffices

to heal the anguish of the nihilist believer that is the young internet surfer

who prefers video games to books.

In the 19th and 20th centuries,

the secular messianism of the "Revolution" absorbed both this need to

transcend itself, and the illusion of total satisfaction for all.

Totalitarianism saw the death drive in the "class enemy," and

repressed all freedom to believe and know.

Underneath the clash

of religions

Demolished, desocialized in the pitiless globalized migration imposed

by ultra-liberalism, or sometimes seemingly well adapted but suffering from

deep, unexpressed emotional crises, adolescents abruptly adopt destructive

conduct under the cover of religious fundamentalism. The nihilist unbinding process destroys the pre-religious

need to believe that constitutes psychic life with and for others and supports

all civilization.

These boundary states

unfold into sociopolitical catastrophes, such as the abjection of extermination

that was the Shoah, a horror that defies reason. They take on new forms in the

globalized world, in the wake of diseases of ideality.

Psychoanalytic

experience is not merely a "comprehensive moralism" (against which

Lacan warns psychoanalysts). In the intimacy of transference-countertransference,

it seeks to refine the interpretation of the potential malignity of the psychic

apparatus in the sense of being capable of radical evil that is revealed in

diseases of ideality. And that, moreover, neither mysticism nor literature have

ignored.

Psychoanalysis reinvents

itself

Souad is a 14-year-old

girl from a Muslim family. She had been monitored for anorexia—the slow killing

of the body, the killing of the abandoned and misunderstood woman and mother in

oneself. Two years later, the state of war in Souad changed. Burqa, silence, and the Internet, where, with unknown accomplices, she

accused her family of being "apostates, worse than disbelievers", and

prepared for her journey "there" to become an occasional wife of

polygamous martyrs or a kamikaze herself.

Souad began interviews

with the mixed multicultural analytical psychotherapy team with a provocation,

saying she was a "scientific mind", strong in math and

physics-chemistry, and whom "only Allah could truly understand ".

Literature "did nothing for her" and she "hated the French and phil classes" that she "skipped whenever

possible". But Souad found pleasure in telling

about herself, playing along with the team; scattered and tenuous transferences

emerged, as with a newly recomposed family, and she was able to laugh with

others and at herself. And to reconnect with French; to tame with words her

destructive urges and suffering senses. Other teenagers supported by the team

attended writing and theater workshops. From them, Souad borrowed a book of Arabic poems translated into French. She began to skip

French courses less. And she put on her jeans again.

Roland Barthes wrote

that if you find meaning in the fullness of a language, "the divine void can no longer

threaten". And, I would add, nor can the excess of the totalitarian

divine. Souad is not there yet. It will take a long

time. She has recently invested in a female therapist, with whom she is in the process of formulating maternal reliance. But how many young people will have the chance

to receive such analytical attention? And to reconnect with an identity in flux?

2. Deprivation vs. possession: 'To have' or 'to be'

Thinkers from Aristotle

all the way to Christian and post-Christian humanism view disability as a defect, 'poverty', lack. And we try to

base the "good life" on compassion, even solidarity, towards this

"lack of being", this impotence, this disability. This compassionate ethic

is prolonged more or less unconsciously even in those contemporary attitudes

that pretend to be the most egalitarian.

Please understand: it

is not a matter of ignoring the pathological, and still less of abolishing it—norms

are unavoidable and make impossible such attitudes—but rather of completing it.

As such, this view

risks locking the disabled subject into the position of a "care

object", of "someone taken care of", at best with

"tenderness", but often through neglect both the scientific knowledge

that identifies and treats specific symptoms, and the creative abilities that

exist, including among those who suffer the most.

In opposition to the

paradigm of "having" (and/or "not having"), however, I argue for the paradigm

of the singularity of the being. Singularity

includes deficit itself as a revealer of the finitude and the borders of the

living, but does not enclose it: singularity is not a deprivation, a lapse or a

sin. The contingency of the singular is positive, as "to be" and "being" come together in it.

The contingency of the singular "handicapped" individual reveals to

me my own singularity of "possessing" said "validity",

which I neither exalt nor deny, but which I accept for good beginning with the

singularity of what is "lacking" or “missing”. It is mortality in

progress that touches me in this; I am it, it falls upon me, I accompany it, I

love it as it is. Via my love for the singular other, I bring it to its

specific, singular development—and to mine, also specific and singular.

The ex-canon Diderot

himself, in another manner which is that of modern humanism, took up this

"positive singularity" when he undertook to transform—for the first

time in the history of the world—the disabled

person as a political subject. The disabled have all the rights, "are

born free and equal in rights", he says, in essence, in his Letter on the Blind for Use by Those Who See (1749). And the Declaration of Human

Rights would take a long time to put into practice this principle, which

through efficient positivity transforms finitude into action in the handicapped

person. The right to "personalized compensation" in the recent French

law addressing disability is an attempt to achieve this ambition.

Yet in order to

fulfill this modern humanist ambition, we have to reinvent the Corpus Mysticumthat

Kant evokes at the end of the Critique of

Pure Reason (1781), so that the singularity of the disabled person can

transform norms themselves into an adaptable dynamic concept—reinventing love as a

union with the singularity of the very other.

In other words: for

the notion and practice of integration, it is important to substitute the

notion and practice of interaction between political subjects, which I

define as a love of the singular. Why this demanding word?

Mark Zuckerberg, the

co-creator of Facebook, recently asserted that it is necessary and possible to

give a “universal income” to every person on Earth. In order to prevent this

happy, universal perspective from degrading into universal egalitarianism and

the banalization of happiness, let us not forget to accompany it with

singularized care for each person’s creativity. Here, I take up again this worn

word, “love”. Love as desire and will so that the singular can elucidate, get

recognition and develop by sharing its own singularity. Much more than just a

stammering solidarity, only this love can lead to positive (and not

"lacking") singularity in a society founded on norms without which,

as I have said, there can be no connection, but it can also change norms.

By opening the

question of love, a "continuously elucidated transference"

accompanying the handicapped person, it is of the training of caregivers

that I am thinking, you understand, and in place of psychoanalysis in

this complex and polemical domain. We will probably come back to this in the

debate.

Allow me to conclude—in

a more personal tone—by recalling the maternal role in this trial. Every

caregiver develops their own psychic bisexuality: feminine and masculine,

maternal reliance and paternal framing, empathy and distance, affects and laws.

3. What freedom?

Finally, what freedom is there in this context?

Freud made but little

mention of freedom, as it was necessarily hampered in his view by the libidinal

prohibitions inherent to civilization. But the possibility that transference-countertransference

has to optimize psychic

life, establish new bonds, and develop creativity is the founding ethic of

psychoanalysis, as Winnicott later formulated. Inspired by a current of Kantian

inspiration, this freedom is an initiative, a restarting of oneself in time: Selbstanfanf (Kant), selfbeginning. It cannot be reduced to merely the entrepreneurial freedom so dear to the

"markets"; it is a freedom-revelation by and in the encounter with the other.

Freedom is not a choice ("and what if it was my

choice to wear a burqa, to go join Daesh? "), it is a construction and a bypassing or transcendence of the self with

and towards the alterity of the other. While old Europe wastes its breath

on impotent accommodations, and on the other side of the Atlantic, the

winner/loser binary and spectacle politics dominate, I say again that the

commitment to psychic life promises to be indispensable, arduous and long-term.

And I am addressing

the students in this room, who are dedicated to the care and support of people,

or to those who, regardless of their profession, are concerned with the link

between the social, the political, and the ethical. There is no other way to

face the surprises of the current anthropological shift. It falls to us, it

falls to YOU, to deepen and to disseminate that vital freedom that we seek to

bring in its most personal sense to those who trust us, and even to those who

spread "radical evil". And for this, we/you must solicit complicity,

disseminate our/your practice, and relentlessly deepen and innovate our/your

research.

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, 21 June 2017